Lung cancer

| Lung cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lung carcinoma |

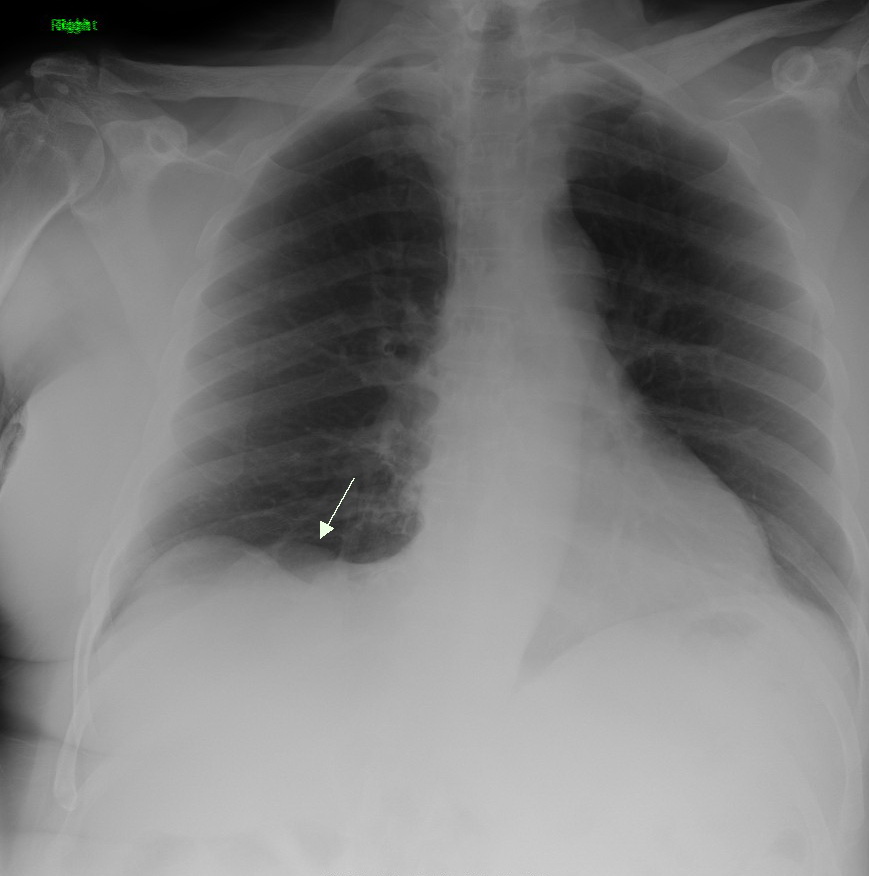

| A chest X-ray showing a tumor in the lung (marked by arrow) | |

| Specialty | Script error: No such module "String2". |

| Symptoms | Coughing (including coughing up blood), weight loss, shortness of breath, chest pains[1] |

| Usual onset | ~70 years[2] |

| Types | Small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)[3] |

| Risk factors | |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging, tissue biopsy[3] |

| Prevention | Avoid smoking, radon gas, asbestos, second-hand smoke, or other forms of air pollution exposure |

| Treatment | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy[3] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate: 10 to 20% (most countries)[6] |

| Frequency | 3.3 million affected as of 2015[7] |

| Deaths | 1.8 million (2020)[6] |

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma[8] (since about 98–99% of all lung cancers are carcinomas), is a malignant lung tumor characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissues of the lung.[9] Lung carcinomas derive from transformed, malignant cells that originate as epithelial cells, or from tissues composed of epithelial cells. Other lung cancers, such as the rare sarcomas of the lung, are generated by the malignant transformation of connective tissues (i.e. nerve, fat, muscle, bone), which arise from mesenchymal cells. Lymphomas and melanomas (from lymphoid and melanocyte cell lineages) can also rarely result in lung cancer.

In time, this uncontrolled growth can metastasize (spreading beyond the lung) either by direct extension, by entering the lymphatic circulation, or via hematogenous, bloodborne spread – into nearby tissue or other, more distant parts of the body.[10] Most cancers that originate from within the lungs, known as primary lung cancers, are carcinomas. The two main types are small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).[3] The most common symptoms are coughing (including coughing up blood), weight loss, shortness of breath, and chest pains.

The vast majority (85%) of cases of lung cancer are due to long-term tobacco smoking.[4] About 10–15% of cases occur in people who have never smoked.[11] These cases are often caused by a combination of genetic factors and exposure to radon gas, asbestos, second-hand smoke, or other forms of air pollution.[4][5][12][13] Lung cancer may be seen on chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans.[14] The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which is usually performed by bronchoscopy or CT-guidance.[3][15]

The major method of prevention is the avoidance of risk factors, including smoking and air pollution.[16] Treatment and long-term outcomes depend on the type of cancer, the stage (degree of spread), and the person's overall health.[14] Most cases are not curable.[3] Common treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.[14] NSCLC is sometimes treated with surgery, whereas SCLC usually responds better to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.[17]

Worldwide in 2020, lung cancer occurred in 2.2 million people and resulted in 1.8 million deaths.[6] It is the most common cause of cancer-related death in both men and women.[18][19] The most common age at diagnosis is 70 years.[2] In most countries the five-year survival rate is around 10 to 20%,[6] while in Japan it is 33%, in Israel 27%, and in the Republic of Korea 25%.[6] Outcomes typically are worse in the developing world.[20]

Signs and symptoms

Early lung cancer often has no symptoms. When symptoms do arise they are often nonspecific respiratory problems – coughing, shortness of breath, and/or chest pain – that can differ from person to person.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those who experience coughing tend to report either a new cough, or an increase in the frequency or strength of a pre-existing cough.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Around a quarter cough up blood, ranging from small streaks in the sputum to large amounts.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Around half of those diagnosed with lung cancer experience shortness of breath, while 25–50% experience a dull, persistent chest pain that remains in the same location over time.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". In addition to respiratory symptoms, some experience systemic symptoms including loss of appetite, weight loss, general weakness, fever, and night sweats.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Some less common symptoms suggest tumors in particular locations. Tumors in the thorax can cause breathing problems by obstructing the trachea or disrupting the nerve to the diaphragm, difficulty swallowing by compressing the esophagus, hoarseness by disrupting the nerves of the larynx, and Horner's syndrome by disrupting the sympathetic nervous system.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Horner's syndrome is also common in tumors at the top of the lung, known as Pancoast tumors, which also cause shoulder pain that radiates down the little finger-side of the arm as well as destruction of the topmost ribs.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Swollen lymph nodes above the collarbone can indicate a tumor that has spread within the chest.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Tumors obstructing bloodflow to the heart can cause superior vena cava syndrome, while tumors infiltrating the area around the heart can cause fluid buildup around the heart, arrythmia, and heart failure.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Around a third of people diagnosed with lung cancer have symptoms caused by metastases in sites distant from the lung.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Lung cancer can metastasize anywhere in the body, with different symptoms depending on the location. Brain metastases can cause headache, nausea, vomiting, seizures, and neurological deficits. Bone metastases can cause pain, bone fractures, and compression of the spinal cord. Metastasis into the bone marrow can deplete blood cells and cause leukoerythroblastosis (immature immune cells in the blood).Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Liver metastases can cause liver enlargement, pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, fever, and weight loss.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Lung tumors also often cause the release of body-altering hormones, which themselves cause unusual symptoms, called paraneoplastic syndromes.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Inappropriate hormone release can cause dramatic shifts in concentrations of blood minerals. Most common is hypercalcemia caused by over-production of parathyroid hormone-related protein or parathyroid hormone. Hypercalcemia can manifest as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, increased thirst, frequent urination, and altered mental status.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those with lung cancer also commonly experience hypokalemia due to inappropriate secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, as well as hyponatremia due to overproduction of antidiuretic hormone or atrial natriuretic peptide.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Around a third of people with lung cancer develop nail clubbing, while up to one in ten experience hypertrophic primary osteoarthropathy. A variety of autoimmune disorders can arise as paraneoplastic syndromes in those with lung cancer, including Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (which causes muscle weakness), sensory neuropathies, muscle inflammation, brain swelling, and autoimmune deterioration of cerebellum, limbic system, or brainstem.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Up to 1 in 12 people with lung cancer have paraneoplastic clotting issues, including migratory venous thrombophlebitis, clots in the heart, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Paraneoplastic syndromes involving the skin and kidneys are rare, each occurring in up to 1% of those with lung cancer.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Diagnosis

A person suspected of having lung cancer will first have various imaging tests done to evaluate the presence, extent, and location of tumors. First, many primary care providers perform a chest X-ray to look for a mass inside the lung.[21] The x-ray may reveal an obvious mass, the widening of the mediastinum (suggestive of spread to lymph nodes there), atelectasis (lung collapse), consolidation (pneumonia), or pleural effusion;[14] however, some lung tumors are not visible by X-ray.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Next, many undergo computed tomography (CT) scanning, which can reveal the sizes and locations of tumors.[21]Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

A definitive diagnosis of lung cancer requires a biopsy of the suspected tissue be histologically examined for cancer cells.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Bronchoscopic or CT-guided biopsy is often used to sample the tumor for histopathology.[15] Additionally, biopsy material of the original tumor or metastases are often tested for their molecular profile to determine eligibility for targeted therapies. Those who cannot undergo a more invasive biopsy procedure may instead have a liquid biopsy taken (i.e. a sample of some body fluid) which may contain circulating tumor DNA that can be used for molecular testing.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Imaging is also used to assess the extent of cancer spread. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning or combined PET-CT scanning is often used to locate metastases in the body. Since PET scanning cannot be used in the brain, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – or CT where MRI is unavailable – to scan the brain for metastases in those with NSCLC and large tumors, or tumors that have spread to the nearby lymph nodes.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". When spread to lymph nodes or to a single site is suspected, the suspected metastasis is often biopsied using a minimally invasive needle biopsy technique – typically using endobronchial ultrasound to guide a bronchoscope equipped with transbronchial needle aspiration.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Primary lung cancers most commonly metastasize to the brain, bones, liver, and adrenal glands.[3]

Lung cancer can often appear as a solitary pulmonary nodule on a chest radiograph. However, the differential diagnosis is wide and many other diseases can also give this appearance, including metastatic cancer, hamartomas, and infectious granulomas caused by tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or coccidioidomycosis.[22] Lung cancer can also be an incidental finding, as a solitary pulmonary nodule on a chest radiograph or CT scan done for an unrelated reason.[23] Clinical practice guidelines recommend specific frequencies (suggested intervals of time between tests) for pulmonary nodule surveillance.[24] CT imaging is not suggested to be used for longer or more frequently than indicated in the clinical guidelines, as any additional surveillance exposes people to increased radiation and is costly.[24]

Classification

| Histological type | Incidence per 100,000 per year |

|---|---|

| All types | 66.9 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 22.1 |

| Squamous-cell carcinoma | 14.4 |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 9.8 |

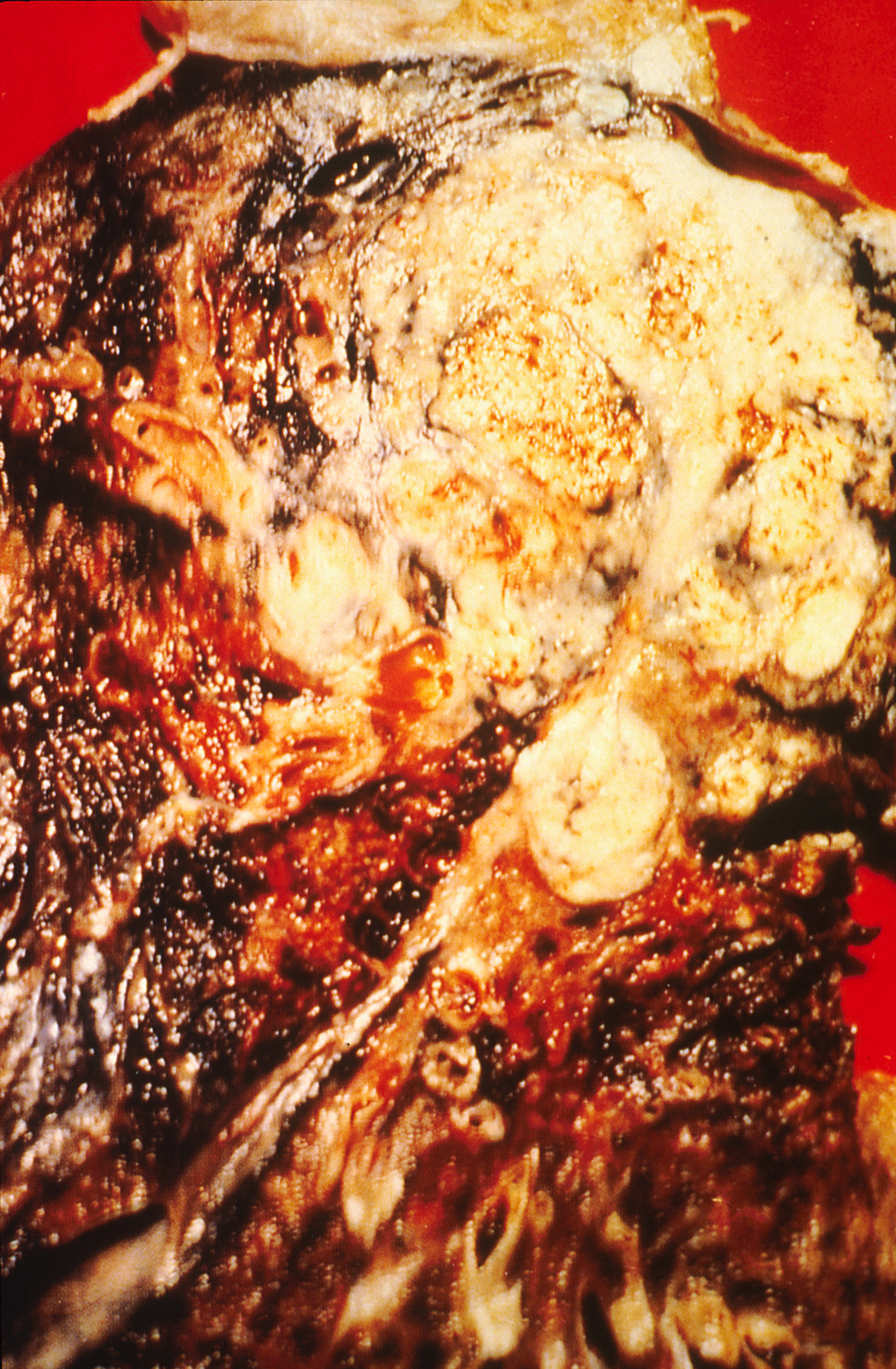

At diagnosis, lung cancers are classified based on the type of cells the tumor is derived from; tumors derived from different cells progress and respond to treatment differently. There are two main types of lung cancer, categorized by the size and appearance of the malignant cells seen by a histopathologist under a microscope: small cell lung cancer (SCLC; 15% of lung cancer diagnoses) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC; 85% of diagnoses).Script error: No such module "Footnotes". In SCLC, cancerous cells appear small with ill-defined boundaries, not much cytoplasm, many mitochondria, and have distinctive nuclei with granular-looking DNA and no visible nucleoli.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Cells contain dense neurosecretory granules (vesicles containing neuroendocrine hormones), which give this tumor an endocrine or paraneoplastic syndrome association.[26] Most cases arise in the larger airways (primary and secondary bronchi).[15] NSCLCs comprise a group of three cancer types: adenocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Nearly 40% of lung cancers are adenocarcinomas, which usually come from peripheral lung tissue.[3] Squamous-cell carcinoma causes about 30% of lung cancers. They typically occur close to large airways. A hollow cavity and associated cell death are commonly found at the center of the tumor.[3] Less than 10% of lung cancers are large-cell carcinomas,Script error: No such module "Footnotes". so named because the cells are large, with excess cytoplasm, large nuclei, and conspicuous nucleoli.[3]

Several lung cancer types are subclassified based on the growth characteristics of the cancer cells. Adenocarcinomas are classified as lepidic (growing along the surface of intact alveolar walls),Script error: No such module "Footnotes". acinar and papillary, or micropapillary and solid pattern. Lepidic adenocarcinomas tend to be least aggressive; micropapillary and solid pattern adenocarcinomas most aggressive.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

In addition to examining cell morphology, biopsies are also often stained with immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis. SLCL is most often confirmed by the presence of chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". The presence of Napsin-A, TTF-1, CK7, and CK20 help confirm the subtype of lung carcinoma.[1]

Around 10% of lung cancers are rarer types.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". These include mixes of the above subtypes like adenosquamous carcinoma.[3] Rare subtypes include carcinoid tumors, bronchial gland carcinomas, and sarcomatoid carcinomas.[3] A subtype of adenocarcinoma, the bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, is more common in females who have not smoked tobacco.[27]

| Histological type | Napsin-A | TTF-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Squamous-cell carcinoma | Negative | Negative |

| Adenocarcinoma | Positive | Positive |

| Small-cell carcinoma | Negative | Positive |

Staging

Lung cancer staging is an assessment of the degree of spread of the cancer from its original source. It is one of the factors affecting both the prognosis and the potential treatment of lung cancer.[28]

SCLC is typically staged with a relatively simple system; cancers are scored as either "limited stage" or "extensive stage". Around a third of people are diagnosed at the limited stage, meaning cancer is confined to one side of the chest, within the scope of a single tolerable radiotherapy field.[28] The other two thirds are diagnosed at the "extensive stage", with cancer spread to both sides of the chest, or to other parts of the body.[28]

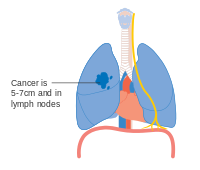

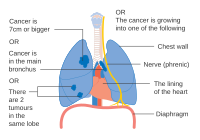

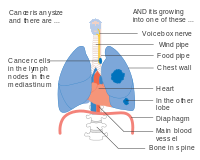

NSCLC – and sometimes SCLC – is typically staged with the American Joint Committee on Cancer's Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging system.[29] The size and extent of the tumor (T), spread to regional lymph nodes (N), and distant metastases (M) are scored individually, and combined to form "stage groups".Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Relatively small tumors are designated T1, which are subdivided by size: tumors ≤ 1 centimeter (cm) across are T1a; 1–2 cm T1b; 2–3 cm T1c. Tumors up to 5 cm across, or those that have spread to the visceral pleura (tissue covering the lung) or main bronchi, are desginated T2. T2a designates 3–4 cm tumors; T2b 4–5 cm tumors. T3 tumors are up to 7 cm across, have multiple nodules in the same lobe of the lung, or invade the chest wall, diaphragm (or the nerve that controls it), or area around the heart.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Tumors that are larger than 7 cm, have nodules spread in different lobes of a lung, or invade the mediastinum (center of the chest cavity), heart, largest blood vessels that supply the heart, trachea, esophagus, or spine are designated T4.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Lymph node staging depends on the extent of local spread: with the cancer metastasized to no lymph nodes (N0), pulmonary or hilar nodes (along the bronchi) on the same side as the tumor (N1), mediastinal or subcarinal lymph nodes (in the middle of the lungs, N2), or lymph nodes on the opposite side of the lung from the tumor (N3).Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Metastases are staged as no metastases (M0), nearby metastases (M1a; the space around the lung or the heart, or the opposite lung), a single distant metastasis (M1b), or multiple metastases (M1c).Script error: No such module "Footnotes". These T, N, and M scores are combined to designate a "stage grouping" for the cancer. Cancers limited to smaller tumors are designated stage I. Those with larger tumors or spread to the nearest lymph nodes are stage II. Those with the largest tumors or extensive lymph node spread are stage III. Cancers that have metastasized are stage IV. Each stage is further subdivided based on the combination of T, N, and M scores.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Around 40% of those diagnosed with NSCLC have stage IV disease at the time of diagnosis.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TNM | Stage group |

|---|---|

| T1a–T1b N0 M0 | IA |

| T2a N0 M0 | IB |

| T1a–T2a N1 M0 | IIA |

| T2b N0 M0 | |

| T2b N1 M0 | IIB |

| T3 N0 M0 | |

| T1a–T3 N2 M0 | IIIA |

| T3 N1 M0 | |

| T4 N0–N1 M0 | |

| N3 M0 | IIIB |

| T4 N2 M0 | |

| M1 | IV |

For both NSCLC and SCLC, the two general types of staging evaluations are clinical staging and surgical staging. Clinical staging is performed before definitive surgery. It is based on the results of imaging studies (such as CT scans and PET scans) and biopsy results. Surgical staging is evaluated either during or after the operation. It is based on the combined results of surgical and clinical findings, including surgical sampling of thoracic lymph nodes.[3]

- Diagrams of main features of staging

One option for stage IIB lung cancer, with T2b; but if tumor is within 2 cm of the carina, this is stage 3

Treatment

Treatment for lung cancer depends on the cancer's specific cell type, how far it has spread, and the person's performance status. Common treatments for early stage cancers include surgical removal of the tumor, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.[1] For later stage cancers, chemotherapy and radiation therapy are combined with newer targeted molecular therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors. All lung cancer treatment regimens are combined with lifestyle changes and palliative care to improve quality of life.

Small-cell lung cancer

Limited-stage SCLC is typically treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". For chemotherapy, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend four to six cycles of a platinum-based chemotherapeutic – cisplatin or carboplatin – combined with either etoposide or irinotecan.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". This is typically combined with thoracic radiation therapy – 45 Gray (Gy) twice-daily – alongside the first two chemotherapy cycles.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". First-line therapy causes remission in up to 80% of those who receive it; however most people relapse with chemotherapy-resistant disease. Those who relapse are given second-line chemotherapies. Topotecan and lurbinectedin are approved by the US FDA for this purpose.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Irinotecan, paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinorelbine, etoposide, and gemcitabine are also sometimes used, and are similarly efficacious.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Prophylactic cranial irradiation can also reduce the risk of brain metastases and improve survival in those with limited-stage disease.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Similarly, extensive-stage SCLC is treated first with etoposide along with either cisplatin or carboplatin. Radiotherapy is used only to shrink tumors that are causing particularly severe symptoms. Combining standard chemotherapy with an immune checkpoint inhibitor can improve survival for a minority of those affected, extending the average person's lifespan by around 2 months.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Non-small-cell lung cancer

For stage I and stage II NSCLC the first line of treatment is often surgical removal of the affected lobe of the lung.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". For those not well enough to tolerate full lobe removal, a smaller chunk of lung tissue can be removed by wedge resection or segmentectomy surgery.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those with centrally located tumors and otherwise-healthy respiratory systems may have more extreme surgery to remove an entire lung (pneumonectomy).Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Experienced thoracic surgeons, and a high-volume surgery clinic improve chances of survival.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those who are unable or unwilling to undergo surgery can instead receive radiation therapy. Stereotactic body radiation therapy is best practice, typically administered several times over 1–2 weeks.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Chemotherapy has little effect in those with stage I NSCLC, and may worsen disease outcomes in those with the earliest disease. In those with stage II disease, chemotherapy is usually initiated six to twelve weeks after surgery, with up to four cycles of cisplatin – or carboplatin in those with kidney problems, neuropathy, or hearing impairment – combined with vinorelbine, pemetrexed, gemcitabine, or docetaxel.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Treatment for those with stage III NSCLC depends on the nature of their disease. Those with more limited spread may undergo surgery to have the tumor and affected lymph nodes removed, followed by chemotherapy and potentially radiotherapy. Those with particularly large tumors (T4) and those for whom surgery is impractical are treated with combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy along with the immunotherapy durvalumab.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Combined chemotherapy and radiation enhances survival compared to chemotherapy followed by radiation, though the combination therapy comes with harsher side effects.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Those with stage IV disease are treated with combinations of pain medication, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Many cases of advanced disease can be treated with targeted therapies depending on the genetic makeup of the cancerous cells. Up to 30% of tumors have mutations in the EGFR gene that result in an overactive EGFR protein;Script error: No such module "Footnotes". these can be treated with EGFR inhibitors osimertinib, erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, or dacomitinib – with osimertinib known to be superior to erlotinib and gefitinib, and all superior to chemotherapy alone.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Up to 7% of those with NSCLC harbor mutations that result in hyperactive ALK protein, which can be treated with ALK inhibitors crizotinib, or its successors alectinib, brigatinib, and ceritinib.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those treated with ALK inhibitors who relapse can then be treated with the third-generation ALK inhibitor lorlatinib.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Up to 5% with NSCLC have overactive MET, which can be inhibited with MET inhibitors capmatinib or tepotinib.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Targeted therapies are also available for some cancers with rare mutations. Cancers with hyperactive BRAF (around 2% of NSCLC) can be treated by dabrafenib combined with the MEK inhibitor trametinib; those with activated ROS1 (around 1% of NSCLC) can be inhibited by crizotinib, lorlatinib, or entrectinib; overactive NTRK (<1% of NSCLC) by entrectinib or larotrectinib; active RET (around 1% of NSCLC) by selpercatinib.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

People whose NSCLC is not targetable by current molecular targeted therapies instead can be treated with combination chemotherapy plus immune checkpoint inhibitors, which prevent cancer cells from inactivating immune T cells. The chemotherapeutic agent of choice depends on the NSCLC subtype: cisplatin plus gemcitabine for squamous cell carcinoma, cisplatin plus pemetrexed for non-squamous cell carcinoma.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Immune checkpoint inhibitors are most effective against cancers that express the protein PD-L1, but are sometimes effective in those that do not.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Treatment with pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, or combination nivolumab plus ipilimumab are all superior to chemotherapy alone against tumors expressing PD-L1.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those who relapse on the above are treated with second-line chemotherapeutics docetaxel and ramucirumab.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Several treatments can be provided via bronchoscopy for the management of airway obstruction or bleeding. If an airway becomes obstructed by cancer growth, options include rigid bronchoscopy, balloon bronchoplasty, stenting, and microdebridement.[32] Laser photosection involves the delivery of laser light inside the airway via a bronchoscope to remove the obstructing tumor.[33]

Palliative care

Integrating palliative care (i.e. medical care focused on improving symptoms and lessening discomfort) into lung cancer treatment from the time of diagnosis improves the survival time and quality of life of those with lung cancer.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". For both NSCLC and SCLC patients, smaller doses of radiation to the chest may be used for symptom control (palliative radiotherapy).[34][35] With adequate physical fitness maintaining chemotherapy during lung cancer palliation offers 1.5 to 3 months of prolongation of survival, symptomatic relief, and an improvement in quality of life, with better results seen with modern agents.[36][37]

Palliative care when added to usual cancer care benefits people even when they are still receiving chemotherapy.[38] These approaches allow additional discussion of treatment options and provide opportunities to arrive at well-considered decisions.[39][40] Palliative care may avoid unhelpful but expensive care not only at the end of life, but also throughout the course of the illness. For individuals who have more advanced disease, hospice care may also be appropriate.[15][40]

Noninvasive interventions

The most effective intervention for avoiding death from lung cancer is to stop smoking; even people who already have lung cancer are encouraged to stop smoking.[41] There is no clear evidence which smoking cessation program is most effective for people who have been diagnosed with lung cancer.[41]

Some weak evidence suggests that certain supportive care interventions (noninvasive) that focus on well-being for people with lung cancer may improve quality of life.[42] Interventions such as nurse follow-ups, psychotherapy, psychosocial therapy, and educational programs may be beneficial, however, the evidence is not strong (further research is needed).[42] Counseling may help people cope with emotional symptoms related to lung cancer.[42] Reflexology may be effective in the short-term, however more research is needed.[42] No evidence has been found to suggest that nutritional interventions or exercise programs for a person with lung cancer result in an improvement in the quality of life that are relevant or last very long.[42]

Exercise training may benefit people with NSCLC who are recovering from lung surgery.[43] In addition, exercise training may benefit people with NSCLC who have received radiotherapy, chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, or palliative care.[44] Exercise training before lung cancer surgery may also improve outcomes.[45] It is unclear if exercise training or exercise programs are beneficial for people who have advanced lung cancer.[46][42] A home-based component in a personalized physical rehabilitation program may be useful for recovery.[44] It is unclear if home-based prehabilitation (before surgery) leads to less adverse events or hospitalization time.[44] Physical rehabilitation with a home-based component may improve recovery after treatment and overall lung health.[44]

Prognosis

| Clinical stage | Five-year survival (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-small-cell lung carcinoma | Small-cell lung carcinoma | |

| IA | 50 | 38 |

| IB | 47 | 21 |

| IIA | 36 | 38 |

| IIB | 26 | 18 |

| IIIA | 19 | 13 |

| IIIB | 7 | 9 |

| IV | 2 | 1 |

Around 19% of people diagnosed with lung cancer survive five years from diagnosis.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Five-year survival is higher in women (22%) than men (16%);Script error: No such module "Footnotes". women tend to be diagnosed with less-advanced disease, and have better outcomes than men diagnosed at the same stage.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". In England and Wales, between 2013 and 2017, overall five-year survival for lung cancer was estimated at 13.8%.[48] Outcomes are generally worse in the developing world.[20] In the US, people with medical insurance are more likely to have a better outcome.[49]

Survival for lung cancer falls as the stage at diagnosis becomes more advanced; the English data suggest that around 70% of patients survive at least a year when diagnosed at the earliest stage, but this falls to just 14% for those diagnosed with the most advanced disease (stage IV).[50]

SCLC is particularly aggressive. Most people treated for SCLC relapse and eventually develop chemotherapy-resistant cancer. The average person diagnosed with SCLC at the limited stage survives 12–20 months from diagnosis; the average person diagnosed at the extensive stage survives around 12 months.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". 10–15% of people with SCLC survive 5 years after diagnosis.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Those with limited stage SCLC that goes into complete remission after chemotherapy and radiotherapy have a 50% chance of brain metastases developing within the next two years – a chance reduced by prophylactic cranial irradiation.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

For NSCLC, the best prognosis is achieved with complete surgical resection of stage-IA disease, with up to 70% five-year survival.[51] The prognosis of patients with NSCLC improved significantly in the last years with the introduction of immunotherapy.[52] 68–92% of those diagnosed with stage I NSCLC survive at least 5 years after diagnosis, as do 53–60% of those diagnosed with stage II NSCLC.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Several personal and disease factors are associated with improved outcomes. Those diagnosed at an earlier disease stage tend to have better prognoses, as do those diagnosed at a younger age. Those who smoke or experience weight loss as a symptom tend to have worse outcomes. Large/active metastases (by PET scan) and tumor mutations in KRAS are associated with reduced survival.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Causes

Cancer develops after genetic damage to DNA and epigenetic changes. Those changes affect the cell's normal functions, including cell proliferation, programmed cell death (apoptosis), and DNA repair. As more damage accumulates, the risk for cancer increases.[53]

Smoking

Tobacco smoking is by far the major contributor to lung cancer, causing 80% to 90% of cases.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Across the developed world, 90% of lung cancer deaths in men and 70% of those in women during 2000 were attributed to smoking.[54] Cigarette smoke contains at least 73 known carcinogens,[55] including benzo[a]pyrene,[56] NNK, 1,3-butadiene, and a radioactive isotope of polonium – polonium-210.[55] Vaping may be a risk factor for lung cancer, but less than that of cigarettes, and further research is necessary due to the length of time it can take for lung cancer to develop following an exposure to carcinogens.[57][58]

Being around tobacoo smoke – called passive smoking – can also cause lung cancer. Living with a tobacco smoker increaes one's risk of developing lung cancer by 24%. An estimated 17% of lung cancer cases in those who do not smoke are caused by high levels of environmental tobacco smoke.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Cannabis smoke contains many of the same carcinogens as those found in tobacco smoke,[59] but the effect of smoking cannabis on lung cancer risk is not clear.[60][61]

Other exposures

Exposure to a variety of other toxic chemicals – typically encountered in certain occupations – are associated with an increased risk of lung cancer.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". In all, occupational exposures to carcinogens are estimated to cause 9–15% of lung cancers.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". A prominent example is asbestos, which causes lung cancer either directly or indirectly by inflamming the lung.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Exposure to all commercially available forms of asbestos increase cancer risk, and cancer risk increases with time of exposure.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Asbestos and cigarette smoking increase risk synergestically – i.e. the risk of someone who smokes and has asbestos exposure dying from lung cancer is much higher than would be expected from adding the two risks together.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Similarly, exposure to radon, a naturally occurring breakdown product of the Earth's uranium, is associated with increased lung cancer risk. This is particularly true in underground miners, who have the greatest exposure; but also in indoor air in residential spaces. Like asbestos, cigarette smoking and radon exposure increase risk synergistically.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Radon exposure is responsible for between 3% and 14% of lung cancer cases.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Several other chemicals encountered in various occupations are also associated with increased lung cancer risk including arsenic used in wood preservation, pesticide application, and some ore smelting; ionizing radiation encountered during uranium mining; vinyl chloride in papermaking; beryllium in jewelers, ceramics workers, missile technicians, and nuclear reactor workers; chromium in stainless steel production, welding, and hide tanning; nickel in electroplaters, glass workers, metal workers, welders, and those who make batteries, ceramics, and jewelry; and diesel exhaust encountered by miners.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Outdoor air pollutants, especially chemicals released from the burning of fossil fuels, increase the risk of lung cancer.[4] Fine particulates (PM2.5) and sulfate aerosols, which may be released in traffic exhaust fumes, are associated with a slightly increased risk.[4][62] For nitrogen dioxide, an incremental increase of 10 parts per billion increases the risk of lung cancer by 14%.[63] Outdoor air pollution is estimated to cause 1–2% of lung cancers.[4]

Indoor air pollution from burning wood, charcoal, or crop residue for cooking and heating has also been linked to an increased risk of developing lung cancer.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified emission from household burning of coal and biomass as "carcinogenic" and "probably carcinogenic" respectively.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". This risk affects about 2.4 billion people worldwide,[64] and it is believed to result in 1.5% of lung cancer deaths.[65]

Genetics

About 8% of lung cancer cases are caused by inherited (genetic) factors.[66] In relatives of people who are diagnosed with lung cancer, the risk is doubled, likely due to a combination of genes.[67] Polymorphisms on chromosomes 5, 6, and 15 have been identified and are associated with an increased risk of lung cancer.[68] Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the genes encoding the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) – CHRNA5, CHRNA3, and CHRNB4 – are of those associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, as well as RGS17 – a gene regulating G-protein signaling.[68] Newer genetic studies, have identified 18 susceptibility loci achieving genome-wide significance. These loci highlight a heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across the histological subtypes of lung cancer, again identifying the cholinergic nicotinic receptors, e.g. CHRNA2.[69]

Pathogenesis

Similar to many other cancers, lung cancer is initiated by either the activation of oncogenes or the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes.[70] Carcinogens cause mutations in these genes that induce the development of cancer.[71]

Mutations in the K-ras proto-oncogene contribute to roughly 10–30% of lung adenocarcinomas.[72][73] Nearly 4% of non-small-cell lung carcinomas involve an EML4-ALK tyrosine kinase fusion gene.[74] The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and tumor invasion.[72] Mutations and amplification of EGFR are common in NSCLC, and they provide the basis for treatment with EGFR inhibitors. Her2/neu is affected less frequently.[72] Other genes that are often mutated or amplified include c-MET, NKX2-1, LKB1, PIK3CA, and BRAF.[72]

Importantly, cancer cells develop resistance to oxidative stress, which enables them to withstand and exacerbate inflammatory conditions that inhibit the activity of the immune system against the tumor.[75][76]

The cell lines of origin are not fully understood.[1] The mechanism may involve the abnormal activation of stem cells. In the proximal airways, stem cells that express keratin 5 are more likely to be affected, typically leading to squamous-cell lung carcinoma. In the middle airways, implicated stem cells include club cells and neuroepithelial cells that express club-cell secretory protein. SCLC may originate from these cell lines[77] or neuroendocrine cells,[1] and it may express CD44.[77] Metastasis of lung cancer requires transition from epithelial to mesenchymal cell type. This may occur through the activation of signaling pathways such as Akt/GSK3Beta, MEK-ERK, Fas, and Par6.[78]

The overwhelming majority of SCLCs have mutations that inactivate the tumor suppressors p53 and RB.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Prevention

Smoking prevention and smoking cessation are effective ways of reducing the risk of lung cancer.

Smoking cessation

Those who smoke can reduce their lung cancer risk by quitting smoking – the risk reduction is greater the longer a person goes without smoking.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Self-help programs tend to have little influence on success of smoking cessation, whereas combined counseling and pharmacotherapy improve cessation rates.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". The U.S. FDA has approved antidepressant therapies and the nicotine replacement varenicline as first-line therapies to aid in smoking cessation. Clonidine and nortriptyline are recommended second-line therapies.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Tobacco control

While in most countries industrial and domestic carcinogens have been identified and banned, tobacco smoking is still widespread. Eliminating tobacco smoking is a primary goal in the prevention of lung cancer, and smoking cessation is an important preventive tool in this process.[79]

Policy interventions to decrease passive smoking in public areas such as restaurants and workplaces have become more common in many Western countries.[80] Bhutan has had a complete smoking ban since 2005[81] while India introduced a ban on smoking in public in October 2008.[82] The World Health Organization has called for governments to institute a total ban on tobacco advertising to prevent young people from taking up smoking.[83] They assess that such bans have reduced tobacco consumption by 16% where instituted.[83]

Screening

Some forms of population screening can allow for earlier detection and treatment of lung cancer cases, reducing deaths from lung cancer. In some trials, screening programs providing low-dose CT scans of individuals at high risk for lung cancer (i.e. people who smoke tobacco and are aged 55 to 74) reduced overall lung cancer mortality.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends yearly screening using low-dose CT in those who have a total smoking history of at least 30 pack-years and are between 55 and 80 years old.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Other prevention strategies

The long-term use of supplemental vitamin A, B vitamins, vitamin D or vitamin E does not reduce the risk of lung cancer.[84] Vitamin C supplementation might reduce the risk of lung cancer.[85][86] Some studies have found vitamins A, B, and E may increase the risk of lung cancer in those who have a history of smoking.[84]

Some studies suggest that people who eat food with a higher proportion of vegetables and fruit tend to have a lower risk,[87][88] but this may be due to confounding – with the lower risk actually due to the association of a high fruit and vegetables diet with less smoking.[89] Several rigorous studies have not demonstrated a clear association between diet and lung cancer risk,[1][88] although meta-analysis that accounts for smoking status may show benefit from a healthy diet.[90]

Epidemiology

Worldwide, lung cancer is the most diagnosed type of cancer, and the leading cause of cancer death.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".Script error: No such module "Footnotes". In 2020, 2.2 million new cases were diagnosed, and 1.8 million people died from lung cancer, representing 18% of all cancer deaths.[6] Lung cancer deaths are expected to rise globally to nearly 3 million annual deaths by 2035, due to high rates of tobacco use and aging populations.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Lung cancer is rare in those younger than 40; from there cancer rates increase with age, stabilizing around age 80.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". The median age of a person diagnosed with lung cancer is 70; the median age of death is 72.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

Lung cancer incidence varies dramatically by geography and sex, with the highest rates in Micronesia, Polynesia, Europe, Asia, and North America; and lowest rates in Africa and Central America.[6] Globally, around 8% of men and 6% of women develop lung cancer in their lifetimes.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". However, the ratio of lung cancer cases in men to women varies dramatically by geography, as high as nearly 12:1 in Belarus, to 1:1 in Brazil, likely due to differences in smoking patterns.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". In the United States, lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer deaths, despite a nearly 50% decrease in the death rate from its peak in 1990.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Lung cancer is the third-most common cancer in the UK (47,968 people were diagnosed with the disease in 2017),[91] and it is the most common cause of cancer-related death (around 34,600 people died in 2018).[92]

In the US, lung cancer rates also vary by racial and ethnic group, with the highest rates in African Americans, and the lowest rates in Hispanics, Native Americans and Asian Americans.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". Also in the US, military veterans have a 25–50% higher rate of lung cancer primarily due to higher rates of smoking.[93] During World War II and the Korean War, asbestos also played a role, and Agent Orange may have caused some problems during the Vietnam War.[94]

Lung cancer risk is dramatically influenced by environmental exposure, namely cigarette smoking, as well as occupational risks in mining, shipbuilding, petroleum refining, and occupations that involve asbestos exposure.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". 85–90% of lung cancer cases are in people who have smoked cigarettes, and 15% of smokers develop lung cancer.Script error: No such module "Footnotes". People who have a long history of smoking have the highest risk of developing lung cancer, with the risk increasing with duration of smoking. The incidence in men rose until the mid-1980s, and has declined since then. In women, the incidence rose until the late 1990s, and has since been stable.[3] Non-smokers' risk of developing lung cancer is also influenced by tobacco smoking; secondhand smoke (i.e. being around tobacco smoke) increases risk of developing lung cancer around 30%, with risk correlated to duration of exposure.Script error: No such module "Footnotes".

For every 3–4 million cigarettes smoked, one lung cancer death can occur.[95] The influence of "Big Tobacco" plays a significant role in smoking.[96] Young nonsmokers who see tobacco advertisements are more likely to smoke.[97] The role of passive smoking is increasingly being recognized as a risk factor for lung cancer,[98] resulting in policy interventions to decrease the undesired exposure of nonsmokers to others' tobacco smoke.[99]

From the 1960s, the rates of lung adenocarcinoma started to rise in relation to other kinds of lung cancer, partially due to the introduction of filter cigarettes. The use of filters removes larger particles from tobacco smoke, thus reducing deposition in larger airways. However, the smoker has to inhale more deeply to receive the same amount of nicotine, increasing particle deposition in small airways where adenocarcinoma tends to arise.[100] Rates of lung adenocarcinoma continues to rise.[101]

History

Lung cancer was uncommon before the advent of cigarette smoking; it was not even recognized as a distinct disease until 1761.[102] Different aspects of lung cancer were described further in 1810.[103] Malignant lung tumors made up only 1% of all cancers seen at autopsy in 1878, but had risen to 10–15% by the early 1900s.[104] Case reports in the medical literature numbered only 374 worldwide in 1912,[105] but a review of autopsies showed the incidence of lung cancer had increased from 0.3% in 1852 to 5.66% in 1952.[106] In Germany in 1929, physician Fritz Lickint recognized the link between smoking and lung cancer,[104] which led to an aggressive antismoking campaign.[107] The British Doctors' Study, published in the 1950s, was the first solid epidemiological evidence of the link between lung cancer and smoking.[108] As a result, in 1964, the Surgeon General of the United States recommended smokers should stop smoking.[109]

The connection with radon gas was first recognized among miners in the Ore Mountains near Schneeberg, Saxony. Silver has been mined there since 1470, and these mines are rich in uranium, with its accompanying radium and radon gas.[110] Miners developed a disproportionate amount of lung disease, eventually recognized as lung cancer in the 1870s.[111] Despite this discovery, mining continued into the 1950s, due to the USSR's demand for uranium.[110] Radon was confirmed as a cause of lung cancer in the 1960s.[112]

The first successful pneumonectomy for lung cancer was performed in 1933.[113] Palliative radiotherapy has been used since the 1940s.[114] Radical radiotherapy, initially used in the 1950s, was an attempt to use larger radiation doses in patients with relatively early-stage lung cancer, but who were otherwise unfit for surgery.[115] In 1997, CHART was seen as an improvement over conventional radical radiotherapy.[116] With SCLC, initial attempts in the 1960s at surgical resection[117] and radical radiotherapy[118] were unsuccessful. In the 1970s, successful chemotherapy regimens were developed.[119]

Research directions

[[File:Template:Ambox globe current red|42px|link=]] | This section needs to be updated. (June 2022) |

The search for new treatment options continues. Many clinical trials involving radiotherapy, surgery, EGFR inhibitors, microtubule inhibitors and immunotherapy are currently underway.[120]

Research directions for lung cancer treatment include immunotherapy,[121][122] which encourages the body's immune system to attack the tumor cells, epigenetics, and new combinations of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, both on their own and together. Many of these new treatments work through immune checkpoint blockade, disrupting cancer's ability to evade the immune system.[121][122]

Ipilimumab blocks signaling through a receptor on T cells known as CTLA-4, which dampens down the immune system. It has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of melanoma, and is undergoing clinical trials for both NSCLC and SCLC.[121]

Other immunotherapy treatments interfere with the binding of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) protein with its ligand PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), and have been approved as first- and subsequent-line treatments for various subsets of lung cancers.[122] Signaling through PD-1 inactivates T cells. Some cancer cells appear to exploit this by expressing PD-L1 in order to switch off T cells that might recognise them as a threat. Monoclonal antibodies targeting both PD-1 and PD-L1, such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab,[78] atezolizumab, and durvalumab[122] are currently in clinical trials for treatment for lung cancer.[121][122]

Epigenetics is the study of small molecular modifications – or "tags" – that bind to DNA and modify gene expression levels. Targeting these tags with drugs can kill cancer cells. Early-stage research in NSCLC using drugs aimed at epigenetic modifications shows that blocking more than one of these tags can kill cancer cells with fewer side effects.[123] Studies also show that giving people these drugs before standard treatment can improve its effectiveness. Clinical trials are underway to evaluate how well these drugs kill lung cancer cells in humans.[123] Several drugs that target epigenetic mechanisms are in development. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in development include valproic acid, vorinostat, belinostat, panobinostat, entinostat, and romidepsin. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors in development include decitabine, azacytidine, and hydralazine.[124]

The TRACERx project is looking at how NSCLC develops and evolves, and how these tumors become resistant to treatment.[125] The project will look at tumor samples from 850 people with NSCLC at various stages including diagnosis, after first treatment, post-treatment, and relapse.[126] By studying samples at different points of tumor development, the researchers hope to identify the changes that drive tumor growth and resistance to treatment. The results of this project will help scientists and doctors gain a better understanding of NSCLC and potentially lead to the development of new treatments for the disease.[125]

For lung cancer cases that develop resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase inhibitors, new drugs are in development. EGFR inhibitors include erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib and icotinib (the last one is only available in China).[127] An alternative signaling pathway, c-Met, can be inhibited by tivantinib and onartuzumab. New ALK inhibitors include crizotinib and ceritinib.[128] If the MAPK/ERK pathway is involved, the BRAF kinase inhibitor dabrafenib and the MAPK/MEK inhibitor trametinib may be beneficial.[129]

The PI3K pathway has been investigated as a target for lung cancer therapy. The most promising strategies for targeting this pathway seem to be selective inhibition of one or more members of the class I PI3Ks, and co-targeted inhibition of this pathway with others such as MEK.[130]

Lung cancer stem cells are often resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. This may lead to relapse after treatment. New approaches target protein or glycoprotein markers that are specific to the stem cells. Such markers include CD133, CD90, ALDH1A1, CD44, and ABCG2. Signaling pathways such as Hedgehog, Wnt, and Notch are often implicated in the self-renewal of stem cell lines. Thus, treatments targeting these pathways may help to prevent relapse.[131]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Horn L, Lovly CM (2018). "Chapter 74: Neoplasms of the lung". In Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (20th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1259644030.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Lu C, Onn A, Vaporciyan AA, et al. (2017). "Chapter 84: Cancer of the Lung". Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (9th ed.). Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 9781119000846.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Alberg AJ, Brock MV, Samet JM (2016). "Chapter 52: Epidemiology of lung cancer". Murray & Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine (6th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4557-3383-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ramada Rodilla JM, Calvo Cerrada B, Serra Pujadas C, Delclos GL, Benavides FG (June 2021). "Fiber burden and asbestos-related diseases: an umbrella review". Gaceta Sanitaria. 36 (2): 173–183. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2021.04.001. PMC 8882348. PMID 34120777.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (May 2021). "Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 71 (3): 209–249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. PMID 33538338.

- ↑ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ White V, Ruperelia P (2020). "28.Respiratory disease". In Feather A, Randall D, Waterhouse M (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 975–982. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5.

- ↑ "Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment – Patient Version (PDQ®)". NCI. 12 May 2015. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ Falk S, Williams C (2010). "Chapter 1". Lung Cancer – the facts (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-19-956933-5.

- ↑ Thun MJ, Hannan LM, Adams-Campbell LL, Boffetta P, Buring JE, Feskanich D, et al. (September 2008). "Lung cancer occurrence in never-smokers: an analysis of 13 cohorts and 22 cancer registry studies". PLOS Medicine. 5 (9): e185. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050185. PMC 2531137. PMID 18788891.

- ↑ Carmona RH (27 June 2006). The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. PMID 20669524. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

Secondhand smoke exposure causes disease and premature death in children and adults who do not smoke.

Retrieved 2014-06-16 - ↑ "Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer. 83. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2015.

There is sufficient evidence that involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) causes lung cancer in humans. ... Involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) is carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 "Lung Carcinoma: Tumors of the Lungs". Merck Manual Professional Edition, Online edition. July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Collins LG, Haines C, Perkel R, Enck RE (January 2007). "Lung cancer: diagnosis and management". American Family Physician. 75 (1): 56–63. PMID 17225705. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ↑ "Lung Cancer Prevention–Patient Version (PDQ®)". NCI. 4 November 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ Chapman S, Robinson G, Stradling J, West S, Wrightson J (2014). "Chapter 31". Oxford Handbook of Respiratory Medicine (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-19-870386-0.

- ↑ de Groot PM, Wu CC, Carter BW, Munden RF (June 2018). "The epidemiology of lung cancer". Translational Lung Cancer Research. 7 (3): 220–233. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2018.05.06. PMC 6037963. PMID 30050761.

- ↑ Romaszko AM, Doboszyńska A (May 2018). "Multiple primary lung cancer: A literature review". Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 27 (5): 725–730. doi:10.17219/acem/68631. PMID 29790681. S2CID 46897665.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Majumder S (2009). Stem cells and cancer (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-387-89611-3. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Diagnosis – Lung Cancer". National Health Service. 1 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ↑ Ost D (2015). "Chapter 110: Approach to the patient with pulmonary nodules". In Grippi MA, Elias JA, Fishman JA, Kotloff RM, Pack AI, Senior RM (eds.). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1685. ISBN 978-0-07-179672-9.

- ↑ Frank L, Quint LE (March 2012). "Chest CT incidentalomas: thyroid lesions, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, and lung nodules". Cancer Imaging. 12 (1): 41–48. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2012.0006. PMC 3335330. PMID 22391408.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society (September 2013). "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ Smokers defined as current or former smokers of more than 1 year of duration. See image page in Commons for percentages in numbers. Reference: Table 2 Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine in: Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA (June 2008). "Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer". Tobacco Control. 17 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.022582. PMC 3044470. PMID 18390646.

- ↑ Rosti G, Bevilacqua G, Bidoli P, Portalone L, Santo A, Genestreti G (March 2006). "Small cell lung cancer". Annals of Oncology. 17 (Suppl. 2): ii5–10. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdj910. PMID 16608983.

- ↑ Raz DJ, He B, Rosell R, Jablons DM (March 2006). "Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a review". Clinical Lung Cancer. 7 (5): 313–22. doi:10.3816/CLC.2006.n.012. PMID 16640802.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "Small Cell Lung Cancer Stages". American Cancer Society. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ "Small Cell Lung Cancer Stages". American Cancer Society. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ "8th edition lung cancer TNM staging summary" (PDF). International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ↑ Van Schil PE, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H (March 2018). "8th TNM edition for lung cancer: a critical analysis". Annals of Translational Medicine. 6 (5): 87. doi:10.21037/atm.2017.06.45. PMC 5890051. PMID 29666810.

- ↑ Lazarus DR, Eapen GA (2014). "Chapter 16: Bronchoscopic interventions for lung cancer". In Roth JA, Hong WK, Komaki RU (eds.). Lung Cancer (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-46874-6.

- ↑ Khemasuwan D, Mehta AC, Wang KP (December 2015). "Past, present, and future of endobronchial laser photoresection". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (Suppl 4): S380–88. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.55. PMC 4700383. PMID 26807285.

- ↑ Fairchild A, Harris K, Barnes E, Wong R, Lutz S, Bezjak A, et al. (August 2008). "Palliative thoracic radiotherapy for lung cancer: a systematic review". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (24): 4001–11. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3312. PMID 18711191.

- ↑ Stevens R, Macbeth F, Toy E, Coles B, Lester JF (January 2015). Stevens R (ed.). "Palliative radiotherapy regimens for patients with thoracic symptoms from non-small cell lung cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD002143. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002143.pub4. PMC 7017846. PMID 25586198.

- ↑ Sörenson S, Glimelius B, Nygren P (2001). "A systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in non-small cell lung cancer". Acta Oncologica. 40 (2–3): 327–39. doi:10.1080/02841860151116402. PMID 11441939.

- ↑ Clegg A, Scott DA, Sidhu M, Hewitson P, Waugh N (2001). "A rapid and systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine and vinorelbine in non-small-cell lung cancer". Health Technology Assessment. 5 (32): 1–195. doi:10.3310/hta5320. PMID 12065068. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Parikh RB, Kirch RA, Smith TJ, Temel JS (December 2013). "Early specialty palliative care – translating data in oncology into practice". The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (24): 2347–51. doi:10.1056/nejmsb1305469. PMC 3991113. PMID 24328469.

- ↑ Kelley AS, Meier DE (August 2010). "Palliative care – a shifting paradigm". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (8): 781–82. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1004139. PMID 20818881.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Prince-Paul M (April 2009). "When hospice is the best option: an opportunity to redefine goals". Oncology. 23 (4 Suppl Nurse Ed): 13–17. PMID 19856592.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Zeng L, Yu X, Yu T, Xiao J, Huang Y (June 2019). "Interventions for smoking cessation in people diagnosed with lung cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD011751. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011751.pub3. PMC 6554694. PMID 31173336.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 Rueda JR, Solà I, Pascual A, Subirana Casacuberta M (September 2011). "Non-invasive interventions for improving well-being and quality of life in patients with lung cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (9): CD004282. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004282.pub3. PMC 7197367. PMID 21901689.

- ↑ Cavalheri V, Burtin C, Formico VR, Nonoyama ML, Jenkins S, Spruit MA, Hill K (June 2019). "Exercise training undertaken by people within 12 months of lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD009955. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009955.pub3. PMC 6571512. PMID 31204439.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Driessen EJ, Peeters ME, Bongers BC, Maas HA, Bootsma GP, van Meeteren NL, Janssen-Heijnen ML (June 2017). "Effects of prehabilitation and rehabilitation including a home-based component on physical fitness, adherence, treatment tolerance, and recovery in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 114: 63–76. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.03.031. PMID 28477748. S2CID 207023145.

- ↑ Sebio Garcia R, Yáñez Brage MI, Giménez Moolhuyzen E, Granger CL, Denehy L (September 2016). "Functional and postoperative outcomes after preoperative exercise training in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 23 (3): 486–97. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivw152. PMID 27226400.

- ↑ Peddle-McIntyre CJ, Singh F, Thomas R, Newton RU, Galvão DA, Cavalheri V (February 2019). "Exercise training for advanced lung cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD012685. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012685.pub2. PMC 6371641. PMID 30741408.

- ↑ Rami-Porta R, Crowley JJ, Goldstraw P (February 2009). "The revised TNM staging system for lung cancer" (PDF). Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 15 (1): 4–9. PMID 19262443. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2012.

- ↑ "Lung cancer survival statistics". Cancer Research UK. 2 April 2020.

- ↑ Slatore CG, Au DH, Gould MK (November 2010). "An official American Thoracic Society systematic review: insurance status and disparities in lung cancer practices and outcomes". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 182 (9): 1195–205. doi:10.1164/rccm.2009-038ST. PMID 21041563.

- ↑ "Lung cancer survival statistics". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Spiro SG (2010). "18.19.1". Oxford Textbook Medicine (5th ed.). OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-920485-4.

- ↑ Nasser NJ, Gorenberg M, Agbarya A (November 2020). "First line Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer". Pharmaceuticals. 13 (11): 373. doi:10.3390/ph13110373. PMC 7695295. PMID 33171686.

- ↑ Brown KM, Keats JJ, Sekulic A, et al. (2010). "Chapter 8". Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (8th ed.). People's Medical Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- ↑ Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, et al. (2006). Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1950–2000: Indirect estimates from National Vital Statistics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-262535-9. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Hecht SS (December 2012). "Lung carcinogenesis by tobacco smoke". International Journal of Cancer. 131 (12): 2724–32. doi:10.1002/ijc.27816. PMC 3479369. PMID 22945513.

- ↑ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC (2013). "Chapter 5". Robbins Basic Pathology (9th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5.

- ↑ Nansseu JR, Bigna JJ (2016). "Electronic Cigarettes for Curbing the Tobacco-Induced Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases: Evidence Revisited with Emphasis on Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa". Pulmonary Medicine. 2016: 4894352. doi:10.1155/2016/4894352. PMC 5220510. PMID 28116156.

This article incorporates text by Nansseu JR, Bigna JJ available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Nansseu JR, Bigna JJ available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Bracken-Clarke D, Kapoor D, Baird AM, Buchanan PJ, Gately K, Cuffe S, Finn SP (March 2021). "Vaping and lung cancer – A review of current data and recommendations". Lung Cancer. 153: 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.12.030. PMID 33429159.

- ↑ Greydanus DE, Hawver EK, Greydanus MM, Merrick J (October 2013). "Marijuana: current concepts(†)". Frontiers in Public Health. 1 (42): 42. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00042. PMC 3859982. PMID 24350211.

- ↑ Owen KP, Sutter ME, Albertson TE (February 2014). "Marijuana: respiratory tract effects". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 46 (1): 65–81. doi:10.1007/s12016-013-8374-y. PMID 23715638. S2CID 23823391.

- ↑ Joshi M, Joshi A, Bartter T (March 2014). "Marijuana and lung diseases". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 20 (2): 173–79. doi:10.1097/mcp.0000000000000026. PMID 24384575. S2CID 8010781.

- ↑ Chen H, Goldberg MS, Villeneuve PJ (October–December 2008). "A systematic review of the relation between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and chronic diseases". Reviews on Environmental Health. 23 (4): 243–97. doi:10.1515/reveh.2008.23.4.243. PMID 19235364. S2CID 24481623.

- ↑ Clapp RW, Jacobs MM, Loechler EL (January–March 2008). "Environmental and occupational causes of cancer: new evidence 2005–2007". Reviews on Environmental Health. 23 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1515/REVEH.2008.23.1.1. PMC 2791455. PMID 18557596.

- ↑ Lim WY, Seow A (January 2012). "Biomass fuels and lung cancer". Respirology. 17 (1): 20–31. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02088.x. PMID 22008241.

- ↑ Sood A (December 2012). "Indoor fuel exposure and the lung in both developing and developed countries: an update". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 33 (4): 649–65. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2012.08.003. PMC 3500516. PMID 23153607.

- ↑ Yang IA, Holloway JW, Fong KM (October 2013). "Genetic susceptibility to lung cancer and co-morbidities". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 5 (Suppl. 5): S454–62. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.08.06. PMC 3804872. PMID 24163739.

- ↑ Dela Cruz CS, Tanoue LT, Matthay RA (2015). "Chapter 109: Epidemiology of lung cancer". In Grippi MA, Elias JA, Fishman JA, Kotloff RM, Pack AI, Senior RM (eds.). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1673. ISBN 978-0-07-179672-9.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Larsen JE, Minna JD (December 2011). "Molecular biology of lung cancer: clinical implications". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 32 (4): 703–40. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2011.08.003. PMC 3367865. PMID 22054881.

- ↑ McKay JD, Hung RJ, Han Y, Zong X, Carreras-Torres R, Christiani DC, et al. (July 2017). "Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes". Nature Genetics. 49 (7): 1126–1132. doi:10.1038/ng.3892. PMC 5510465. PMID 28604730.

- ↑ Cooper WA, Lam DC, O'Toole SA, Minna JD (October 2013). "Molecular biology of lung cancer". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 5 (Suppl. 5): S479–90. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.08.03. PMC 3804875. PMID 24163741.

- ↑ Tobias J, Hochhauser D (2010). "Chapter 12". Cancer and its Management (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-4051-7015-4.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM (September 2008). "Lung cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (13): 1367–80. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0802714. PMID 18815398.

- ↑ Aviel-Ronen S, Blackhall FH, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS (July 2006). "K-ras mutations in non-small-cell lung carcinoma: a review". Clinical Lung Cancer. 8 (1): 30–38. doi:10.3816/CLC.2006.n.030. PMID 16870043.

- ↑ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC (2013). "Chapter 5". Robbins Basic Pathology (9th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5.

- ↑ Takahashi N, Chen HY, Harris IS, Stover DG, Selfors LM, Bronson RT, et al. (June 2018). "Cancer Cells Co-opt the Neuronal Redox-Sensing Channel TRPA1 to Promote Oxidative-Stress Tolerance". Cancer Cell. 33 (6): 985–1003.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2018.05.001. PMC 6100788. PMID 29805077.

- ↑ Vlahopoulos S, Adamaki M, Khoury N, Zoumpourlis V, Boldogh I (February 2019). "Roles of DNA repair enzyme OGG1 in innate immunity and its significance for lung cancer". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 194: 59–72. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.09.004. PMC 6504182. PMID 30240635.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Mulvihill MS, Kratz JR, Pham P, Jablons DM, He B (February 2013). "The role of stem cells in airway repair: implications for the origins of lung cancer". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 32 (2): 71–74. doi:10.5732/cjc.012.10097. PMC 3845611. PMID 23114089.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Powell CA, Halmos B, Nana-Sinkam SP (July 2013). "Update in lung cancer and mesothelioma 2012". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 188 (2): 157–66. doi:10.1164/rccm.201304-0716UP. PMC 3778761. PMID 23855692.

- ↑ Dela Cruz CS, Tanoue LT, Matthay RA (December 2011). "Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 32 (4): 605–44. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2011.09.001. PMC 3864624. PMID 22054876.

- ↑ McNabola A, Gill LW (February 2009). "The control of environmental tobacco smoke: a policy review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (2): 741–58. doi:10.3390/ijerph6020741. PMC 2672352. PMID 19440413.

- ↑ Pandey G (February 2005). "Bhutan's smokers face public ban". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ↑ Pandey G (2 October 2008). "Indian ban on smoking in public". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 "UN health agency calls for total ban on tobacco advertising to protect young" (Press release). United Nations News service. 30 May 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Alsharairi NA (March 2019). "The effects of dietary supplements on asthma and lung cancer risk in smokers and non-smokers: a review of the literature". Nutrients. 11 (4): 725. doi:10.3390/nu11040725. PMC 6521315. PMID 30925812.

- ↑ Luo J, Shen L, Zheng D (August 2014). "Association between vitamin C intake and lung cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis". Scientific Reports. 4 (6161): 6161. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E6161L. doi:10.1038/srep06161. PMC 5381428. PMID 25145261.

- ↑ Shareck M, Rousseau MC, Koushik A, Siemiatycki J, Parent ME (February 2017). "Inverse association between dietary intake of selected carotenoids and vitamin C and risk of lung cancer". Frontiers in Oncology. 7 (23): 23. doi:10.3389/fonc.2017.00023. PMC 5328985. PMID 28293540.

- ↑ Alberg AJ, Ford JG, Samet JM (September 2007). "Epidemiology of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition)". Chest. 132 (3 Suppl): 29S–55S. doi:10.1378/chest.07-1347. PMID 17873159.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Key TJ (January 2011). "Fruit and vegetables and cancer risk". British Journal of Cancer. 104 (1): 6–11. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6606032. PMC 3039795. PMID 21119663.

- ↑ Bradbury KE, Appleby PN, Key TJ (July 2014). "Fruit, vegetable, and fiber intake in relation to cancer risk: findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 100 (Suppl. 1): 394S–98S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071357. PMID 24920034.

- ↑ Sun Y, Li Z, Li J, Li Z, Han J (March 2016). "A Healthy Dietary Pattern Reduces Lung Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 8 (3): 134. doi:10.3390/nu8030134. PMC 4808863. PMID 26959051.

- ↑ "Cancer incidence statistics". Cancer Research UK. 13 May 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lung cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. 14 May 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Honoring veterans with good health". Gibbs Cancer Center & Research Institute. 7 November 2014. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ "Lung Cancer As It Affects Veterans And Military". Lung Cancer Alliance. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Proctor RN (March 2012). "The history of the discovery of the cigarette-lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll". Tobacco Control. 21 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050338. PMID 22345227.

- ↑ Lum KL, Polansky JR, Jackler RK, Glantz SA (October 2008). "Signed, sealed and delivered: "big tobacco" in Hollywood, 1927-1951". Tobacco Control. 17 (5): 313–23. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.025445. PMC 2602591. PMID 18818225. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009.

- ↑ Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF (October 2011). "Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (10): CD003439. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. PMC 7173757. PMID 21975739.

- ↑ Dubin S, Griffin D (2020). "Lung Cancer in Non-Smokers". Missouri Medicine. 117 (4): 375–379. PMC 7431055. PMID 32848276.

- ↑ Kemp FB (July–September 2009). "Smoke free policies in Europe. An overview". Pneumologia. 58 (3): 155–58. PMID 19817310.

- ↑ Charloux A, Quoix E, Wolkove N, Small D, Pauli G, Kreisman H (February 1997). "The increasing incidence of lung adenocarcinoma: reality or artefact? A review of the epidemiology of lung adenocarcinoma". International Journal of Epidemiology. 26 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1093/ije/26.1.14. PMID 9126499.

- ↑ Kadara H, Kabbout M, Wistuba II (January 2012). "Pulmonary adenocarcinoma: a renewed entity in 2011". Respirology. 17 (1): 50–65. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02095.x. PMC 3911779. PMID 22040022.

- ↑ Morgagni GB (1761). De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis. OL 24830495M.

- ↑ Bayle GL (1810). Recherches sur la phthisie pulmonaire (in français). Paris. OL 15355651W.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Witschi H (November 2001). "A short history of lung cancer". Toxicological Sciences. 64 (1): 4–6. doi:10.1093/toxsci/64.1.4. PMID 11606795.

- ↑ Adler I (1912). Primary Malignant Growths of the Lungs and Bronchi. New York: Longmans, Green, and Company. OCLC 14783544. OL 24396062M., cited in Spiro SG, Silvestri GA (September 2005). "One hundred years of lung cancer". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 172 (5): 523–29. doi:10.1164/rccm.200504-531OE. PMID 15961694.

- ↑ Grannis FW. "History of cigarette smoking and lung cancer". smokinglungs.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ Proctor R (2000). The Nazi War on Cancer. Princeton University Press. pp. 173–246. ISBN 978-0-691-00196-8.

- ↑ Doll R, Hill AB (November 1956). "Lung cancer and other causes of death in relation to smoking; a second report on the mortality of British doctors". British Medical Journal. 2 (5001): 1071–81. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5001.1071. PMC 2035864. PMID 13364389.

- ↑ US Department of Health Education and Welfare (1964). "Smoking and health: report of the advisory committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service" (PDF). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Greaves M (2000). Cancer: the Evolutionary Legacy. Oxford University Press. pp. 196–97. ISBN 978-0-19-262835-0.

- ↑ Greenberg M, Selikoff IJ (February 1993). "Lung cancer in the Schneeberg mines: a reappraisal of the data reported by Harting and Hesse in 1879". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 37 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1093/annhyg/37.1.5. PMID 8460878.

- ↑ Samet JM (April 2011). "Radiation and cancer risk: a continuing challenge for epidemiologists". Environmental Health. 10 (Suppl. 1): S4. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-10-S1-S4. PMC 3073196. PMID 21489214.

- ↑ Horn L, Johnson DH (July 2008). "Evarts A. Graham and the first pneumonectomy for lung cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (19): 3268–75. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8260. PMID 18591561.

- ↑ Edwards AT (March 1946). "Carcinoma of the bronchus". Thorax. 1 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1136/thx.1.1.1. PMC 1018207. PMID 20986395.

- ↑ Kabela M (1956). "[Experience with radical irradiation of bronchial cancer]" [Experience with radical irradiation of bronchial cancer]. Ceskoslovenska Onkologia (in Deutsch). 3 (2): 109–15. PMID 13383622.