Tobacco in the United States

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

| History |

| Chemistry |

| Biology |

| Personal and social impact |

| Production |

Tobacco has a long history in the United States.

Tobacco distribution is measured in the United States using the term, "tobacco outlet density."[1] An estimated 34.3 million people, or 14% of all adults (aged 18 years or older), in the United States smoked cigarettes in 2015. By state, in 2015, smoking prevalence ranged from between 9.1% and 12.8% in Utah to between 23.7% and 27.4% in West Virginia. By region, in 2015, smoking prevalence was highest in the Midwest (18.7%) and South (15.3%) and lowest in the West (12.4%). Men tend to smoke more than women. In 2015, 16.7% of men smoked compared to 13.6% of women.[2] In 2018, 13.7% of U.S. adults were smokers.[3]

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, accounting for approximately 443,000 deaths, or 1 of every 5 deaths, in the United States each year.[4] Cigarette smoking alone has cost the United States $96 billion in direct medical expenses and $97 billion in lost productivity per year or an average of $4,260 per adult smoker.

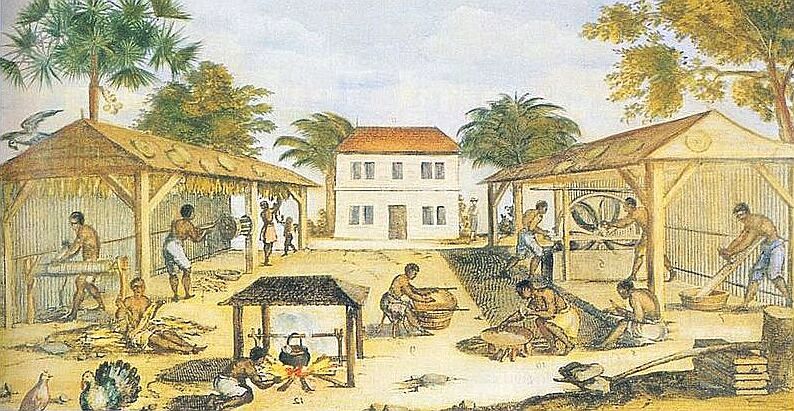

History of commercial tobacco

Commercial tobacco production dates back to the 17th century when the first commercial crop was planted. The industry originated in the production of tobacco for pipes and snuff. Different war efforts in the world created a shift in demand and production of tobacco in the world and the American colonies. With the advent of the American Revolution trade with the colonies was interrupted which shifted trade to other countries in the world. During this shift there was an increase in demand for tobacco in the United States, where the demand for tobacco in the form of cigars and chewing tobacco increased. Other wars, such as the War of 1812 would introduce the Andalusian cigarette to the rest of Europe. This, accompanied with the American Civil War changed the production of tobacco in America to the manufactured cigarette.

John Rolfe

In 1612, John Rolfe arrived in Jamestown to find the colonists there struggling and starving.[5] He had brought with him a new species of tobacco known as nicotiana tabacum.[6] This species was preferable to the native nicotiana rustica as it was much smoother.[7] It is unknown where John Rolfe got the seeds for this new species of tobacco, as the sale of the seeds to a non-Spaniard was punishable by death.[6] However, this new nicotiana tabacum proved to be very popular in England and the first shipment was sent in 1614. By 1639, 750 tons of tobacco had been shipped to England.[8]

Cultivation methods

In the period of 1619 to 1629, the average tobacco farmer was expected to produce 712 pounds of tobacco in a year. By the period of 1680 to 1699, the output per worker was 1,710 pounds of tobacco in a year.[9] These increases in productivity were brought about primarily from relocation and better farming techniques. While early tobacco cultivation techniques were relatively rudimentary, colonial farmers quickly developed more efficient techniques.[10] Tobacco will wear out the soil in just a few years and this necessitated farmers to relocate from coastal areas up rivers in the Chesapeake Bay area.[11] Production was further increased by the use of slave labor on larger farms. On the frontier, hired help would both farm the tobacco and protect farms from Indian raids.[12]

Expansion of trade

In 1621, King James prohibited the production of tobacco in England, limiting its growth to the colonies in America.[12] While it would take many years for this to take effect, it influenced other policies. In reaction to this, the colonies would pass legislation like the Tobacco Inspection Act of 1730 in Virginia as a way to control the production of tobacco and raise its price. Legislation was also passed as a way of ensuring that low-quality trash tobacco was not being shipped or used for the payment of taxes.[13] This series of legislation on both sides of the Atlantic to exert control over the tobacco industry would continue until the American Revolutionary War.[12]

Tobacco's economic decline

Due to the Revolutionary War, Southern exports dropped by 39% from the upper South and almost 50% from the lower South. Lack of domestic market growth exacerbated these effects and a stagnated tobacco industry failed to fully recover as cotton became the main cash crop of the south going forward.[14]

Economic impact of the early tobacco industry

Economic growth in the early colonies

Tobacco played a huge role in the development of the early Chesapeake Colonies. With the early tobacco boom in Virginia and the expansion of trade with England, the value of tobacco soared and provided an incentive for a large influx of colonists. In Virginia, the rough climate made it difficult for the colonists to produce crops that were necessary for survival. Due to this difficulty, the colonists lacked a source of income and food.[11] The colonists of Virginia began to grow tobacco. Tobacco brought the colonists a large source of revenue that was used to pay taxes and fines, purchase slaves, and to purchase manufactured goods from England.[12] As the colonies grew, so did their production of tobacco. Slaves and indentured servants were brought into the colonies to participate in tobacco farming.[15] It has been said that some colonies would have continued to fail had it not been for the production of tobacco.[16][17] Tobacco provided the early colonies with an opportunity for expansion and economic success.[11][12]

British mercantilism and monopolization of the tobacco trade

As early as 1621, only 14 years after the establishment of a colony in Virginia and just 9 years after John Rolfe discovered the economic potential of tobacco in America, British merchants were on the march in an attempt to control the tobacco trade.[12] A measure was introduced into the British Parliament in 1621 with two major components: a restriction on tobacco importation from anywhere with the exception of Virginia and the British West Indies and an edict that tobacco was not to be grown and cultivated anywhere else within England.[18] The objective of the merchants was to monopolize and control all means of tobacco distribution within Europe and throughout the world. By doing so it was possible to secure a stable return on investment for the American Colonies and profit tremendously within Europe. The British merchants influenced economies using the power of the nation-state to influence and protect business interests. In exchange, taxes were levied in order to fund political interests. The bill that the merchants put forward in 1621 to Parliament was a classic example of the power and influence of mercantilism.

The measure passed the House of Commons although it was defeated in the House of Lords. Despite this defeat the measure eventually was pushed through by proclamation from King James.[12] Ironically King James had very strong opinions against the use of tobacco, pointing to the ill health effects and social impact of those that used tobacco [19] Despite these grievances the King was then able to capture import duties on tobacco and in exchange monopoly power was granted to the merchants.

The measures also prevented any foreign ships from carrying colonial tobacco.[12] This monopolization became extremely profitable and flourished during the 1600s. The economy of Virginia was extremely dependent on the tobacco trade. So much so that subtle shifts in demand and prices dramatically affected the Virginian economy as a whole.[11] This led to several booms and busts related to tobacco. The price of tobacco dropped from 6.50 pennies per pound in the 1620s down to as low as .80 pennies per pound in the 1690s. This downward trending triggered a whole series of crop controls and government sponsored price manipulations throughout the 1600s to try to stabilize pricing, but to no avail.[12]

Cash crop

By the mid 1620s tobacco became the most common commodity for bartering due to the increasing scarcity of gold and silver and the decreasing value of wampum from forgery and overproduction. In order to help with accounting and standardizing trade, colonial government officials would rate tobacco and compare its weight into values of pounds, shillings, and pence.[20] The popularity of American tobacco increased dramatically in the colonial period eventually leading to English goods being traded equally with tobacco. Because England's climate did not allow for the same quality of tobacco as that grown in America, the colonists did not have to worry about scarcity of tobacco. This eventually led to tobacco being the main form of trade with England.

Imports of tobacco into England increased from 60,000 pounds in 1622 to 500,000 pounds in 1628, and to 1,500,000 pounds in 1639. Such dramatic growth in demand for tobacco eventually led to overproduction of the commodity, and in turn extreme devaluation of tobacco. To compensate for the loss of value, farmers would add dirt and leaves to increase the weight, but lowering the quality.[21] From the 1640s to the 1690s the value of tobacco would be highly unstable, government officials would help stabilize tobacco by reducing the amount of tobacco produced, standardizing the size of a tobacco hogshead, and prohibiting shipments of bulk tobacco. Eventually the tobacco currency would stabilize in the early 1700s but would be short lived as farmers started cutting back on growing tobacco. In the 1730s tobacco crops were being replaced with food crops as the colonies moved closer to revolution with England.[11]

Current smoking among adults in 2016 (nation)

According to the research, for every 100 U.S adults, age 18 or older, more than 15 smoked cigarettes in 2016. In other words, there are about 37.8 million cases of cigarette smokers in the United States. More than 16 million Americans are living with a smoking-related disease. However, the number of smokers in 2016 has decreased to 15.5% which is a 5.4% difference from 2005. This shows an increase in the number of smokers who have quit. Men smoke at a higher rate than women. At every 100 adults, men nearly got 4 more cases than women.[22]

Overall, it is estimated that 5.66 million adults in the US population reported current vaping 2.3%. From those users in the population, more than 2.21 million were current cigarette smokers (39.1%), more than 2.14 million were former smokers (37.9%), and more than 1.30 million were never smokers (23.1%).[23]

Statistics in 2018 estimated that about 14.9% of adults (18 and over) had ever used e-cigarettes, and around 3.2% of all adults in the United States were current e-cigarette users. These same stats also noted that 34 million U.S. adults were current smokers, with E-cigarette usage being highest among current smokers and former smokers who are attempting or have recently quit cigarettes.[24]

The 2010s within the United states saw both the advent and uptick in the prevalence of vaping among American youths. Electronic cigarettes are one of the most up and coming forms of nicotine delivery for U.S Consumers. The first commercial e-cigarette hit the markets in 2006.[25] Reports in 2018 estimated that youth vaping is present among 27.5% of the youth population. This is a stark comparison to the 5.5% of reported youths within the United States who smoke combustible nicotine such as cigarettes.[26]

| The prevalence of smoking by age[27] | |

| 18 – 24 years old | 8.0% |

| 25 – 44 years old | 16.7% |

| 45 – 64 years old | 17.0% |

| 65 and older | 8.2% |

| Age | % of Population who Vape[26] |

|---|---|

| 13 Year Olds | 6% |

| 14 Year Olds | 10% |

| 15 Year Olds | 15% |

| 16 Year Old | 22% |

| 17 Year olds | 24% |

| 18 Year Olds | 25% |

| The prevalence of smoking by educational level[27] | |

| Fewer years of education (no diploma) | 24.1% |

| GED certificate | 35.3% |

| High school diploma | 19.6% |

| Some college (no degree) | 17.7% |

| Associate degree | 14.0% |

| Undergraduate degree | 6.9% |

| Graduate degree | 4.0% |

| The prevalence of smoking by race/ethnicity[27] | |

| Non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives | 20.9% |

| Non-Hispanic Other races | 19.7% |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 14.9% |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 15.5% |

| Hispanics | 8.8% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 7.2% |

Legislation

On February 4, 2009, the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 was signed into law, which raised the federal tax rate for cigarettes on April 1, 2009 from $0.39 per pack to $1.01 per pack.[28][29]

- Cigarette taxes in the United States

- No Net Cost Tobacco Act of 1982

- Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act

- Planters' Protective Association

- Reality Check (organization)

- Tobacco MSA (Alabama)

- Tobacco MSA (Hawaii)

- Tobacco MSA (New York)

- Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement

- Tobacco Price Support Program

- Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee

Lobbying and organizations

There has been intensive lobbying in the US to portray smoking as a harmless activity. The Insider is a 1999 feature film about the production of a news segment exposing Big Tobacco. The raising influence Social Media has on new generations of teens has provided new platforms for anti-smoking organizations. A prime example is TruthOrange sponsoring YouTube's content creators to include their ads. As well as using YouTube's ads algorithm to provide their target audience, teens, a thirty second ad.

Lobbyists include:

- Advancement of Sound Science Center

- DEBUNKIFY

- Tobacco Institute

- Golden LEAF Foundation

- Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

- WhiteLies.tv

- Truth (anti-tobacco campaign)

Costs

443,000 Americans die of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke each year. For every smoking-related death, another 20 people suffer with a smoking-related disease. (2011)[30]

California's adult smoking rate has dropped nearly 50% since the state began the nation's longest-running tobacco control program in 1988. California saved $86 billion in health care costs by spending $1.8 billion on tobacco control, a 50:1 return on investment over its first 15 years of funding its tobacco control program.[30]

Companies and products

Some of the notable tobacco companies in the US are:

- U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company

- Flue-cured tobacco

- Burley tobacco

- Marlboro, a brand of cigarettes made by Philip Morris USA

Critics

An estimated half a million children worked in the fields of America picking food as of 2012, although the precise number working in tobacco fields is unknown. In eastern North Carolina, children have been interviewed as young as fourteen who worked harvesting tobacco, and recent news reports describe children as young as nine and ten doing such work. Federal law provides no minimum age for work on small farms with parental permission, and children ages twelve and up may work for hire on any size farm for unlimited periods outside school hours. According to Human Rights Watch, farm-work is the most hazardous occupation open to children.[31][32]

See also

- Prevalence of tobacco consumption#United States

- List of smoking bans in the United States

- Smoker Protection Law

- Steven C. Parrish, the Senior Vice President of Philip Morris

- C. C. Little - tobacco researcher

- Tobacco-Free Pharmacies

- Drug policy of Oregon#Tobacco

- History of women in the United States#Virginia

References

- ↑ Yu, D; Peterson, N. A; Sheffer, M. A; Reid, R. J; Schnieder, J. E (2010). "Tobacco outlet density and demographics: Analysing the relationships with a spatial regression approach". Public Health. 124 (7): 412–6. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2010.03.024. PMID 20541232.

- ↑ "Smoking and Tobacco Use Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ "Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States". 15 December 2020.

- ↑ Adult Cigarette Smoking in the United States: Current Estimate Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- ↑ "Our Ancestors in Jamestown, Virginia". Genealogical Gleanings. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Rolfe, John (d. 1622)". www.encyclopediavirginia.org.

- ↑ Shifflett, Crandall. "John Rolfe (1585-1622)". Virtual Jamestown. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Borio, Gene (6 September 2018). "No Title". archive.tobacco.org.

- ↑ Menard, R. R. (1985). Economy and Society in Early Maryland. New York. pp. 448–50, 462.

- ↑ McGregory, Jerrilyn (1997-04-01). Wiregrass Country. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 30–. ISBN 9780878059263. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Tobacco in Colonial Virginia". www.encyclopediavirginia.org.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Pecquet, Gary M. (2003). "British Mercantilism and Crop Controls in the Tobacco Colonies: A Study of Rent-Seeking Costs" (PDF). Cato Journal. 22. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ General Assembly. "Tobacco Inspection of 1730". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Soltow, James H. (1994). "Cotton as Religion, Politics, Law, Economics and Art". Agricultural History. 68 (2): 6–19. JSTOR 3744399.

- ↑ Menard, R. R. (2007). "Plantation Empire: How Sugar and Tobacco Planters Built Their Industries and Raised an Empire". Agricultural History. 81 (3): 319. doi:10.3098/ah.2007.81.3.309. JSTOR 20454724. S2CID 154101847.

- ↑ "The Roanoke Colonies". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Starving Time". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Middleton, A.P. (1953). "Tobacco Coast". Newport News, VA. Mariners' Museum.

- ↑ "BLASTE Appendix, King James I of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco". www.laits.utexas.edu.

- ↑ "LEARN NC has been archived". www.learnnc.org.

- ↑ Borio, Gene (6 September 2018). "No Title". archive.tobacco.org.

- ↑ Health, CDC's Office on Smoking and (2018-09-24). "CDC - Fact Sheet - Adult Cigarette Smoking in the United States - Smoking & Tobacco Use". Smoking and Tobacco Use. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ↑ Mayer, Margaret; Reyes-Guzman, Carolyn; Grana, Rachel; Choi, Kelvin; Freedman, Neal D. (2020-10-13). "Demographic Characteristics, Cigarette Smoking, and e-Cigarette Use Among US Adults". JAMA Network Open. 3 (10): e2020694. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20694. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 8094416. PMID 33048127.

- ↑ "Products - Data Briefs - Number 365 - April 2020". www.cdc.gov. 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ "The Evolution and Impact of Electronic Cigarettes". National Institute of Justice. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Quintero, Nandeeni Patel and Diana (2019-11-22). "The youth vaping epidemic: Addressing the rise of e-cigarettes in schools". Brookings. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States". cdc.gov. 15 December 2020.

- ↑ Frank, Pallone (4 February 2009). "H.R.2 - 111th Congress (2009-2010): Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009". www.thomas.gov.

- ↑ http://www.allamericanpatriots.com/health/48749802-american-lung-association-celebrates-public-health-victory American Lung Association Celebrates Public Health Victory

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Adult Smoking in the US CDC September 2011

- ↑ The Hidden Victims of Tobacco HRW September 5, 2012

- ↑ Children in the Fields: North Carolina Tobacco Farms NBC August 9, 2012

Further reading

- Brandt, Allan. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America (2007).

- Breen, T. H. (1985). Tobacco Culture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00596-6. Source on tobacco culture in 18th-century Virginia pp. 46–55.

- Burns, Eric. The Smoke of the Gods: A Social History of Tobacco (Temple University Press, 2007)

- Hahn, Barbara. Making Tobacco Bright: Creating an American Commodity, 1617-1937 (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011) 248 pages; examines how marketing, technology, and demand figured in the rise of Bright Flue-Cured Tobacco, a variety first grown in the inland Piedmont region of the Virginia-North Carolina border.

- Kluger, Richard. Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War (1996), Pulitzer Prize.

- Milov, Sarah (2019). The Cigarette: A Political History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674241213.

- Price, Jacob M. "The rise of Glasgow in the Chesapeake tobacco trade, 1707-1775." William and Mary Quarterly (1954) pp: 179-199. in JSTOR

- Tilley, Nannie May The Bright Tobacco Industry 1860–1929 ISBN 0-405-04728-2.

External links

- CS1: long volume value

- Articles with short description

- Wikipedia introduction cleanup from January 2022

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All pages needing cleanup

- Articles covered by WikiProject Wikify from January 2022

- All articles covered by WikiProject Wikify

- Tobacco in the United States

- Economy of the United States

- Smoking in the United States