Nicotine poisoning

| Nicotine poisoning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nicotine | |

| Specialty | Script error: No such module "String2". |

Nicotine poisoning describes the symptoms of the toxic effects of nicotine following ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact. Nicotine poisoning can potentially be deadly, though serious or fatal overdoses are rare.[1] Historically, most cases of nicotine poisoning have been the result of use of nicotine as an insecticide.[2][3] More recent cases of poisoning typically appear to be in the form of Green Tobacco Sickness, or due to unintended ingestion of tobacco or tobacco products or consumption of nicotine-containing plants.[4][5][6]

Standard textbooks, databases, and safety sheets consistently state that the lethal dose of nicotine for adults is 60 mg or less (30–60 mg), but there is overwhelming data indicating that more than 500 mg of oral nicotine is required to kill an adult.[7]

Children may become ill following ingestion of one cigarette;[8] ingestion of more than this may cause a child to become severely ill.[5][9] The nicotine in the e-liquid of an electronic cigarette can be hazardous to infants and children, through accidental ingestion or skin contact.[10] In some cases children have become poisoned by topical medicinal creams which contain nicotine.[11]

People who harvest or cultivate tobacco may experience Green Tobacco Sickness (GTS), a type of nicotine poisoning caused by skin contact with wet tobacco leaves. This occurs most commonly in young, inexperienced tobacco harvesters who do not consume tobacco.[4][12]

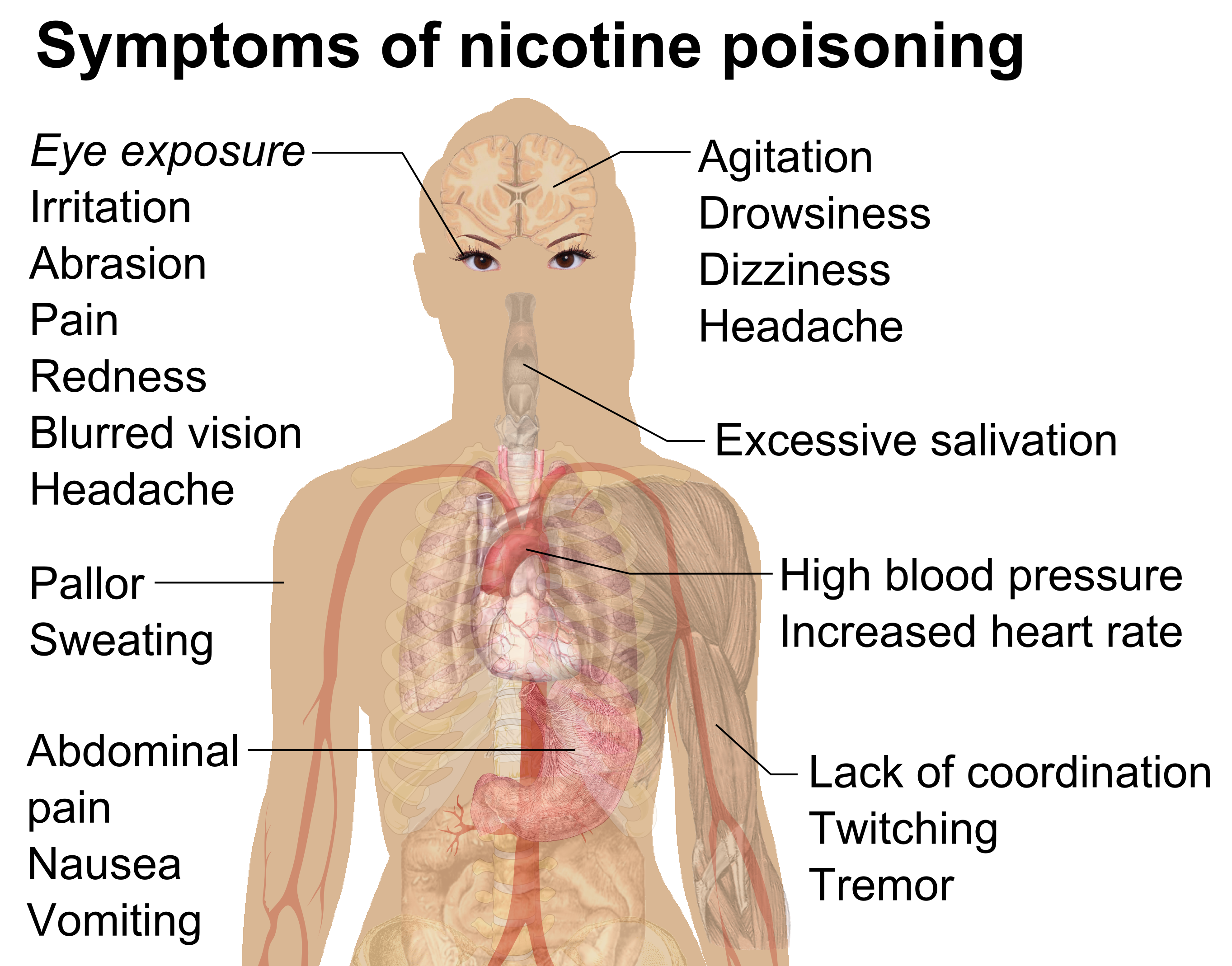

Signs and symptoms

Nicotine poisoning tends to produce symptoms that follow a biphasic pattern. The initial symptoms are mainly due to stimulatory effects and include nausea and vomiting, excessive salivation, abdominal pain, pallor, sweating, hypertension, tachycardia, ataxia, tremor, headache, dizziness, muscle fasciculations, and seizures.[4] After the initial stimulatory phase, a later period of depressor effects can occur and may include symptoms of hypotension and bradycardia, central nervous system depression, coma, muscular weakness and/or paralysis, with difficulty breathing or respiratory failure.[1][4][14]

From September 1, 2010 to December 31, 2014, there were at least 21,106 traditional cigarette calls to US poison control centers.[15] During the same period, the ten most frequent adverse effects to traditional cigarettes reported to US poison control centers were vomiting (80.0%), nausea (9.2%), drowsiness (7.8%), cough (7.2%), agitation (6.6%), pallor (3.0%), tachycardia (2.5%), diaphoresis (1.5%), dizziness (1.5%), and diarrhea (1.4%).[15] 95% of traditional cigarette calls were related to children 5 years old or less.[15] Most of the traditional cigarette calls were a minor effect.[15]

Calls to US poison control centers related to e-cigarette exposures involved inhalations, eye exposures, skin exposures, and ingestion, in both adults and young children.[16] Minor, moderate, and serious adverse effects involved adults and young children.[15] Minor effects correlated with e-cigarette liquid poisoning were tachycardia, tremor, chest pain and hypertension.[17] More serious effects were bradycardia, hypotension, nausea, respiratory paralysis, atrial fibrillation and dyspnea.[17] The exact correlation is not fully known between these effects and e-cigarettes.[17] 58% of e-cigarette calls to US poison control centers were related to children 5 years old or less.[15] E-cigarette calls had a greater chance to report an adverse effect and a greater chance to report a moderate or major adverse effect than traditional cigarette calls.[15] Most of the e-cigarette calls were a minor effect.[15]

From September 1, 2010 to December 31, 2014, there were at least 5,970 e-cigarette calls to US poison control centers.[15] During the same period, the ten most frequent adverse effects to e-cigarettes and e-liquid reported to US poison control centers were vomiting (40.4%), eye irritation or pain (20.3%), nausea (16.8%), red eye or conjunctivitis (10.5%), dizziness (7.5%), tachycardia (7.1%), drowsiness (7.1%), agitation (6.3%), headache (4.8%), and cough (4.5%).[15]

E-cigarette exposure cases in the US National Poison Data System increased greatly between 2010 and 2014, peaking at 3,742 in 2014, fell in 2015 though 2017, and then between 2017 and 2018 e-cigarette exposure cases increased from 2,320 to 2,901.[18] The majority of cases (65%) were in children under age five and 15% were in ages 5-24.[18] Approximately 0.1% of cases developed life-threatening symptoms.[18]

Toxicology

The LD50 of nicotine is 50 mg/kg for rats and 3 mg/kg for mice. 0.5–1.0 mg/kg can be a lethal dosage for adult humans, and 0.1 mg/kg for children.[19][20] However the widely used human LD50 estimate of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg was questioned in a 2013 review, in light of several documented cases of humans surviving much higher doses; the 2013 review suggests that the lower limit causing fatal outcomes is 500–1000 mg of ingested nicotine, corresponding to 6.5–13 mg/kg orally.[21] An accidental ingestion of only 6 mg may be lethal to children.[22]

It is unlikely that a person would overdose on nicotine through smoking alone. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stated in 2013: "There are no significant safety concerns associated with using more than one [over the counter] OTC [nicotine replacement therapy] NRT at the same time, or using an OTC NRT at the same time as another nicotine-containing product—including a cigarette."[23][24][25] Ingestion of nicotine pharmaceuticals, tobacco products, or nicotine containing plants may also lead to poisoning.[4][5][6] Smoking excessive amounts of tobacco has also led to poisoning; a case was reported where two brothers smoked 17 and 18 pipes of tobacco in succession and were both fatally poisoned.[2] Spilling an extremely high concentration of nicotine onto the skin can result in intoxication or even death since nicotine readily passes into the bloodstream following skin contact.[26][27]

The recent rise in the use of electronic cigarettes, many forms of which are designed to be refilled with nicotine-containing "e-liquid" supplied in small plastic bottles, has renewed interest in nicotine overdoses, especially the possibility of young children ingesting the liquids.[28] A 2015 Public Health England report noted an "unconfirmed newspaper report of a fatal poisoning of a two-year old child" and two published case reports of children of similar age who had recovered after ingesting e-liquid and vomiting.[28] They also noted case reports of suicides by nicotine, where adults drank liquid containing up to 1,500 mg of nicotine.[28] They recovered (helped by vomiting), but an ingestion apparently of about 10,000 mg was fatal, as was an injection.[28] They commented that "Serious nicotine poisoning seems normally prevented by the fact that relatively low doses of nicotine cause nausea and vomiting, which stops users from further intake."[28] Four adults died in the US and Europe, after intentionally ingesting liquid.[29] Two children, one in the US in 2014 and another in Israel in 2013, died after ingesting liquid nicotine.[30]

The discrepancy between the historically stated 60-mg dose and published cases of nicotine intoxication has been noted previously (Matsushima et al. 1995; Metzler et al. 2005). Nonetheless, this value is still widely accepted over the 500mg figure as the basis for safety regulations of tobacco and other nicotine-containing products (such as the EU wide TPD, set at a maximum of 20mg/ml.

Pathophysiology

The symptoms of nicotine poisoning are caused by effects at nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Nicotine is an agonist at nicotinic acetylcholine receptor which are present in the central and autonomic nervous systems, and the neuromuscular junction. At low doses nicotine causes stimulatory effects on these receptors, however, higher doses or more sustained exposures can cause inhibitory effects leading to neuromuscular blockade.[4][31]

It is sometimes reported that people poisoned by organophosphate insecticides experience the same symptoms as nicotine poisoning. Organophosphates inhibit an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase, causing a buildup of acetylcholine, excessive stimulation of all types of cholinergic neurons, and a wide range of symptoms. Nicotine is specific for nicotinic cholinergic receptors only and has some, but not all of the symptoms of organophosphate poisoning.

Diagnosis

Increased nicotine or cotinine (the nicotine metabolite) is detected in urine or blood, or serum nicotine concentrations increase.

Treatment

The initial treatment of nicotine poisoning may include the administration of activated charcoal to try to reduce gastrointestinal absorption. Treatment is mainly supportive and further care can include control of seizures with the administration of a benzodiazepine, intravenous fluids for hypotension, and administration of atropine for bradycardia. Respiratory failure may necessitate respiratory support with rapid sequence induction and mechanical ventilation. Hemodialysis, hemoperfusion or other extracorporeal techniques do not remove nicotine from the blood and are therefore not useful in enhancing elimination.[4] Acidifying the urine could theoretically enhance nicotine excretion,[32] although this is not recommended as it may cause complications of metabolic acidosis.[4]

Prognosis

The prognosis is typically good when medical care is provided and patients adequately treated are unlikely to have any long-term sequelae. However, severely affected patients with prolonged seizures or respiratory failure may have ongoing impairments secondary to the hypoxia.[4][33] It has been stated that if a patient survives nicotine poisoning during the first 4 hours, they usually recover completely.[14] At least at "normal" levels, as nicotine in the human body is broken down, it has an approximate biological half-life of 1–2 hours. Cotinine is an active metabolite of nicotine that remains in the blood for 18–20 hours, making it easier to analyze due to its longer half-life.[34]

See also

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Lavoie FW, Harris TM (1991). "Fatal nicotine ingestion". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (3): 133–136. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(91)90318-a. PMID 2050970.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 McNally WD (1920). "A report of five cases of poisoning by nicotine". Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 5: 213–217.

- ↑ McNally WD (1923). "A report of seven cases of nicotine poisoning". Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 8: 83–85.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (September 2009). "Nicotinic plant poisoning". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (8): 771–781. doi:10.1080/15563650903252186. PMID 19778187. S2CID 28312730.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Smolinske SC, Spoerke DG, Spiller SK, Wruk KM, Kulig K, Rumack BH (January 1988). "Cigarette and nicotine chewing gum toxicity in children". Human Toxicology. 7 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1177/096032718800700105. PMID 3346035. S2CID 27707333.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Furer V, Hersch M, Silvetzki N, Breuer GS, Zevin S (March 2011). "Nicotiana glauca (tree tobacco) intoxication--two cases in one family". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 7 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0102-x. PMC 3614112. PMID 20652661.

- ↑ Mayer B (January 2014). "How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century". Archives of Toxicology. 88 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0. PMC 3880486. PMID 24091634.

- ↑ Martin T, Morgan S, Edwards WC (August 1986). "Evaluation of normal brain sodium levels in cattle". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 28 (4): 308–309. PMID 3750811.

- ↑ Malizia E, Andreucci G, Alfani F, Smeriglio M, Nicholai P (April 1983). "Acute intoxication with nicotine alkaloids and cannabinoids in children from ingestion of cigarettes". Human Toxicology. 2 (2): 315–316. doi:10.1177/096032718300200222. PMID 6862475. S2CID 29806143.

- ↑ Brown CJ, Cheng JM (May 2014). "Electronic cigarettes: product characterisation and design considerations". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii4–i10. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051476. PMC 3995271. PMID 24732162.

- ↑ Davies P, Levy S, Pahari A, Martinez D (December 2001). "Acute nicotine poisoning associated with a traditional remedy for eczema". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 85 (6): 500–502. doi:10.1136/adc.85.6.500. PMC 1718993. PMID 11719343.

- ↑ Gehlbach SH, Williams WA, Perry LD, Woodall JS (September 1974). "Green-tobacco sickness. An illness of tobacco harvesters". JAMA. 229 (14): 1880–1883. doi:10.1001/jama.1974.03230520022024. PMID 4479133.

- ↑ Detailed reference list is located at a separate image page.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Saxena K, Scheman A (December 1985). "Suicide plan by nicotine poisoning: a review of nicotine toxicity". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 27 (6): 495–497. PMID 4082460.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 15.9 Chatham-Stephens K, Law R, Taylor E, Kieszak S, Melstrom P, Bunnell R, et al. (December 2016). "Exposure Calls to U. S. Poison Centers Involving Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Cigarettes-September 2010-December 2014". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 12 (4): 350–357. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0563-7. PMC 5135675. PMID 27352081.

- ↑ Chatham-Stephens K, Law R, Taylor E, Melstrom P, Bunnell R, Wang B, et al. (April 2014). "Notes from the field: calls to poison centers for exposures to electronic cigarettes--United States, September 2010-February 2014". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 63 (13): 292–293. PMC 5779356. PMID 24699766.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 Nelluri BK, Murphy K, Mookadam F (May 2015). "Electronic cigarettes and cardiovascular risk: hype or up in smoke?". Future Cardiology. 11 (3): 271–273. doi:10.2217/fca.15.13. PMID 26021631.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 18.2 Wang B, Liu S, Persoskie A (June 2020). "Poisoning exposure cases involving e-cigarettes and e-liquid in the United States, 2010-2018". Clinical Toxicology. 58 (6): 488–494. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1661426. PMC 7061080. PMID 31496321.

- ↑ IPCS INCHEM

- ↑ Okamoto M, Kita T, Okuda H, Tanaka T, Nakashima T (July 1994). "Effects of aging on acute toxicity of nicotine in rats". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 75 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00316.x. PMID 7971729.

- ↑ Mayer B (January 2014). "How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century". Archives of Toxicology. 88 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0. PMC 3880486. PMID 24091634.

- ↑ Jimenez Ruiz CA, Solano Reina S, de Granda Orive JI, Signes-Costa Minaya J, de Higes Martinez E, Riesco Miranda JA, et al. (August 2014). "The electronic cigarette. Official statement of the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) on the efficacy, safety and regulation of electronic cigarettes". Archivos de Bronconeumologia. 50 (8): 362–367. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2014.02.006. PMID 24684764.

- ↑ "Consumer Updates: Nicotine Replacement Therapy Labels May Change". FDA. April 1, 2013.

- ↑ Woolf A, Burkhart K, Caraccio T, Litovitz T (1996). "Self-poisoning among adults using multiple transdermal nicotine patches". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 34 (6): 691–698. doi:10.3109/15563659609013830. PMID 8941198.

- ↑ Labelle A, Boulay LJ (March 1999). "An attempted suicide using transdermal nicotine patches". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 44 (2): 190. PMID 10097845.

- ↑ Lockhart LP (1933). "Nicotine poisoning". British Medical Journal. 1 (3762): 246–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3762.246-c. PMC 2368002.

- ↑ Faulkner JM (1933). "Nicotine poisoning by absorption through the skin". JAMA. 100 (21): 1664–1665. doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740210012005.

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Hitchman SC, Hajek P, McRobbie H (August 2015). "E-cigarettes: an evidence update" (PDF). UK: Public Health England. p. 63.

- ↑ Hua M, Talbot P (December 2016). "Potential health effects of electronic cigarettes: A systematic review of case reports". Preventive Medicine Reports. 4: 169–178. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.06.002. PMC 4929082. PMID 27413679.

- ↑ Biyani S, Derkay CS (August 2015). "E-cigarettes: Considerations for the otolaryngologist". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 79 (8): 1180–1183. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.032. PMID 25998217.

- ↑ Zevin S, Gourlay SG, Benowitz NL (1998). "Clinical pharmacology of nicotine". Clinics in Dermatology. 16 (5): 557–564. doi:10.1016/s0738-081x(98)00038-8. PMID 9787965.

- ↑ Rosenberg J, Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Wilson KM (October 1980). "Disposition kinetics and effects of intravenous nicotine". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 28 (4): 517–522. doi:10.1038/clpt.1980.196. PMID 7408411. S2CID 10531903.

- ↑ Rogers AJ, Denk LD, Wax PM (February 2004). "Catastrophic brain injury after nicotine insecticide ingestion". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 26 (2): 169–172. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.05.006. PMID 14980338.

- ↑ Bhalala O (Spring 2003). "Detection of Cotinine in Blood Plasma by HPLC MS/MS". MIT Undergraduate Research Journal. 8: 45–50.